If

[tabgroup] [tab title=”Letter from the Editor”] [heading style=”1″]Asking the right questions[/heading]Letter from the Editor

Asking the right questions

Somewhere there is a boy standing on a rainy playground at a cloudy sunset hanging onto a fistful of colorful balloons that stand out defiantly among the asphalt and gray-brown mulch land that he inhabits.

As the rain wears rivulets into his skin and the stones around him, it occurs to him suddenly in the way perspective does that his entire life is one enormous recursive hinge. There is a question that will send him deeper and deeper down layers of nested paths, some twisted and dark, others light of step and smooth, others still every variation and gradient between, if he makes a choice. If.

If is a foundational argument in computer logic, a corporate slogan, an excuse to many, but above all it is the question humanity has always tried to answer, the clever heroes of myth and equally great philosophers and scientists asking and answering hypotheses through experimentation and adventure.

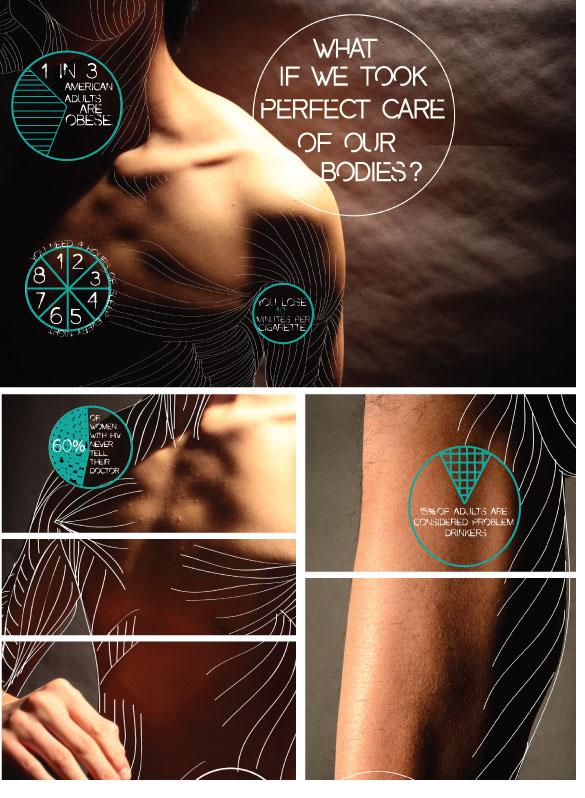

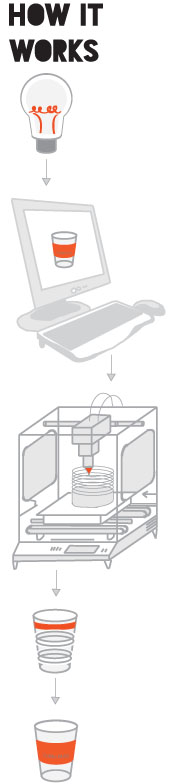

In this issue of Southpaw we have attempted to answer the multitudes of ifs that spring up in light of new inventions, new discoveries. If the 3D printer becomes cheap, what will it mean for manufacturing? What if we could take care of our bodies perfectly? Erase memories?

Though we cannot answer them in any conclusive way — it is very hard to determine the future, even from the most sure signs — we believe that to try will spur thought, and thought will lead to action and action will lead to an outcome.

We cannot determine our future but we can alter it’s course by asking the right questions that will come up in the future, if they do.

In the end, our future is as mysterious as the questions we raise — endlessly hypothetical, uncertain and terribly, wonderfully obfuscated. If, for instance, clever Odysseus had known, sailing away after a decade of war from the ruined walls of Troy, that all awaiting him were 10 more years of wander and slaughter, how could he have continued? Yet we still seek our fortune, as he sought his.

In the end, our future is determined as much by the questions we ask as at answers to them. Whether they plumb the depths of human existence — “If my world was a simulation…” — or assess simple opportunity cost, all have an effect on the future of our own lives and society as a whole.

In the end, it could be as simple a query as ‘If I let go…” sending the brightly colored balloons floating gently into the now quiet and darkening skies.

– Maria Kalaitzandonikes, editor-in-chief

[/tab][tab title=”Pangaea”]

[heading style=”1″]”Imagine there’s no countries. It’s not hard to do. Nothing to kill or die for.” – John Lennon[/heading]

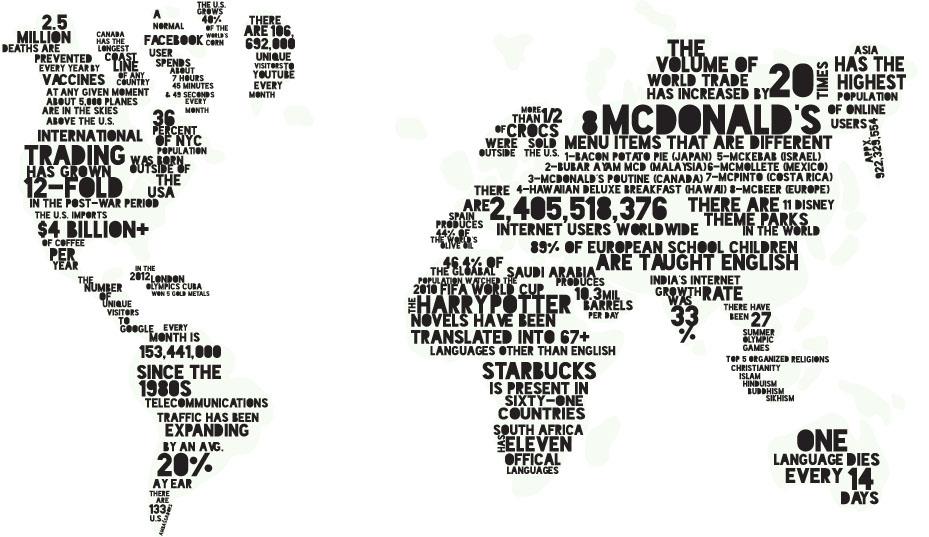

The American company is in more than half of the countries across the world. One would think the seemingly tremendous presence of American culture would threaten local cultures globally, but senior Nahush Katti said in India, this isn’t the case. He paralleled a McDonald’s in India to a Panera Bread Company here.

“McDonald’s is considered pretty high end [in India,]” Katti said. “You don’t have the dollar menu or the equivalent of that. … [McDonald’s] obviously … can’t really serve a Big Mac because in India [where there is Hinduism] you can’t eat cows, so they wouldn’t make any money if they sold a Big Mac or something like that.”

Katti said he sees other American products, such as Nike, Adidas and Ralph Lauren, when he visits India as well, as American products have so successfully globalized. He never feels as if he’s in America while he’s overseas, however, due to the fact that the products still have a link to Indian culture and way of life; the US isn’t the only one benefiting.

The products are sold “through local retailers, so it’s India’s version of … MC Sports or those types of things,” Katti said. “It’s not like it’s actually taking any business or anything away from local markets. It doesn’t bother me.”

Junior Charlie Gan attended Chinese school for seven years, starting when he was in first grade. Gan already knew the language because his parents spoke to him in Chinese his entire life, so he attended Chinese school to learn reading and writing.

His Sunday mornings were devoted to the extra school. He said he didn’t enjoy going because of all the extra homework piled on top of his already heavy school load. Chinese school was “that annoying thing that you had to do every single week,” he said.

But looking back on the experience, despite the lack of enthusiasm for the workload, Gan said he is glad he learned to read and write in Chinese.

World Studies teacher Greg Irwin believes culture is important for individuals, but a nation having specific “norms” expected to be followed is not helpful for anyone.

“[Culture in] Columbia is gonna be different than New York City, it’s different than Los Angeles, so even within a country, there is fairly significant diversity,” Irwin said. “The value I place on top … is individual freedom of thought, expression, whether it’s in politics, religion or style. To me, if a culture allows that, it’s a healthy culture.”

When describing his culture, Irwin talks about his ideas based on American cultural norms as opposed to his Irish and Scottish ancestors. For him, culture emulates how he feels people should see themselves in relation to those around them. Gan has learned this lesson. What used to sometimes be an annoyance is now how he defines himself.

“When I was little, it was always like, ‘Oh, you’re Chinese,’ so … I didn’t really like my culture because I was different from everyone else,” Gan said. “But now that I’m in high school, I would say that it’s a very important part of me.”

By Maddie Magruder

[/tab][tab title=”Climate Change”]

[heading style=”1″]It’s getting hot in here: Extreme weather changes become more prominent[/heading]

As snow fell heavily in Columbia, Mo. on Feb. 21, climate change’s cries suddenly became louder. The locally dubbed “Snowpocalypse” occurred after a considerably mild winter and caused four snow days for RBHS, power outages in the city and poor road conditions, branching from a snow storm that moved across the south.

The severe winter storm comprised of snow, sleet and ice caused Gov. Jay Nixon to declare a state of emergency in Missouri. Only three days prior, it was sunny and the high temperature reached almost 60 degrees.

According to epa.gov, Earth’s temperature has changed significantly over time. The average temperature rose by 1.4ºF during the past century. While the increase may not seem like much, by 2100 the Environmental Protection Agency projects the global temperature to increase by 4-11ºF depending on the level of greenhouse gas emissions. The increase in temperature implies more frequent and extreme heat waves and events, such as those seen in Columbia.

Sophomore and Student Environmental Coalition member Kristen Tarr believes the problem of climate change and global warming will not “fix itself,” and the future state of the earth worries her.

“I don’t think many people actually understand how important of an issue this is,” Tarr said. “Our standards of life are much higher with electricity. … Making any kind of change is hard … you have to be highly motivated and passionate, and I don’t think many people currently are with this issue. I’m afraid that no one will really do anything about it until the problem comes face-to-face with us and it is too late.”

Although many may believe the effects have little impact, in 2011 an unprecedented 14 disastrous weather events resulted in an estimated $53 billion in damage — not including health costs, according to the National Resources Defense Council. Daniel Lashof, director of the Climate and Clean Air program at the NRDC said extreme weather events are not only starting to become more common, but also more intense.

“These kinds of [weather] effects [will] continue to take place. [The increase in temperature] would dramatically alter the climate beyond anything that human civilization is accustomed to,” Lashof said. “It would have huge impacts on people’s lives and their health. It would directly affect these things and indirectly affect things like agriculture, storms and land droughts.”

And many promote this change. The European Union plans to ban all cars from city centers by 2050 in order to cut down on carbon dioxide emissions. The EU hopes to target zero diesel and petrol fueled cars in future cities in 40 years and create alternative means of transportation.

In 2008, 40 percent of United States fossil-fuel emissions came from the consumption of petroleum products. While some say society must abandon gas-fueled vehicles in order to aid in the climate change efforts, Lashof said this is not the case.

“With reducing driving you would certainly help reduce emissions, but I think the biggest source of change will come from changing … the fuel efficiency of our cars by 2025. … Then we can reduce emissions further,” Lashof said. “Planes are perhaps the most challenging. There are technologies that are being developed like biofuels and liquid hydrogen that can be used and engineered for airplanes, but that will be one of the more difficult sources to use. Unfortunately it’s a really small source.”

Senior Noor Khreis visits her family in Jordan at least once every other year, which requires the use of air travel. Yet, because she has become so adapted to her comfortable lifestyle in the U.S. and the ability she has to visit her family, climate change’s detrimental effects doesn’t cause her to worry about her home or her family in Jordan, and she’s not quite ready to give up her lifestyle.

“If giving up my lifestyle to improve climate change means that I can’t see my family [in Jordan], then I wouldn’t be [willing to] give it up. [I’m not concerned with the environment’s future] because as a society we are too lazy. We love technology. We love the easy life. We don’t care for the environment anymore,” Khreis said. “Well, yeah [climate change] may happen, and I can worry about that. But who knows if those theories are true? I figure just worry when the time comes, and if we can reduce technology usage to prevent it, then we should … but no one really thinks about it much, [and] if I don’t think about [climate change] enough, how can I be scared of it?”

However, even though such an embargo would bring change, Tarr said it wouldn’t be reasonable for people to give up daily luxuries. Instead, she thinks it would be more efficient for the U.S. government to impose a carbon tax.

“The world’s demand for energy and the many technologies that benefit from it outweigh the price of us lowering the amount of energy used,” Tarr said. “The price of a nuclear reactor costs, like, $14 billion, but the cost to run the plant is very low. … Taxing the coal plants on the amount of carbon dioxide they emit is a cost effective way of generating revenue to turn around and spend on nuclear reactors. This would also make the factory owners take a step back and look at the full social effect of their emissions.”

Places such as British Columbia, India and the U.K. all hold a carbon or fossil fuel tax. Boulder, Colo. implemented the U.S.’ first tax on carbon emissions from electricity, on April 1, 2007.

According to bouldercolorado.gov, the tax costs the average household about $1.33 per month, with households that use renewable energy receiving an offsetting discount. The tax was scheduled to expire at the end of 2012, but in November of that year the city approved a five-year extension to the tax. Since then, California and Maryland have discussed and proposed the implementation of similar taxes.

Even though Lashof believes these changes would improve the current state of climate change, he said there will always be time to make a change.

“We’re rapidly approaching a point where it would be too late to prevent serious damage and a point where serious consequences have already occurred,” Lashof said. “But it matters how much carbon pollution we put into the air. … I wouldn’t really say that there will ever be a point of no return. The most important initiatives we can take are to change the way we produce and use energy and solar power and to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels and eventually replace fossil fuels with renewable energy sources.”

By Jacqueline LeBlanc

[/tab][tab title=”Disease”]

[heading style=”1″]Healing Progress[/heading]

Animal hosts transferred many of these diseases to humans, which were often spread among closely related species or came from distantly related species humans have come in close contact with. And according to research done in the journal Nature, scientists know little about the origins of many longstanding

human diseases. A study in Nature examined suspected sources of diseases found in tropical and moderate climates, and the authors of the study were able to identify five stages infectious diseases transition through, from those found strictly in animals to those that infect humans only.

Stage one: the pathogen remains within the animal and not in the human at all.

Stage two: the pathogen can be transmitted from animals to humans but not between humans.

Stage three: the pathogen can be transferred between humans, causing occasional outbreaks, but dies easily.

Stage four: the pathogen undergoes more frequent and extended transmission between humans.

Stage five: the pathogen becomes human exclusive and has made the jump from animal to human.

When the Black Plague struck, according to www.deathblack.wordpress.com, by 1350, almost a third of Europe’s population had died, with between an estimated 100 and 200 million deaths worldwide. At the height of the polio epidemic in 1952, according to www.kidshealth.org, nearly 60,000 cases of polio with more than 3,000 deaths were reported in the United States alone. Smallpox, which originated some 10,000 years ago, came and went in waves, killing relentlessly until the first vaccine was introduced in the early 18th century. This was a turning point in the medical field as the first vaccination for smallpox led to similar vaccines created for later diseases such as yellow fever, mumps, rubella and tetanus, revolutionizing the way future deadly diseases would be treated.

Doctors, politicians and laypeople worry and wonder about the diseases of the future. Rumors of “superbugs” and drug-resistant diseases and retroviruses can leave a patient trembling in their open-backed hospital gown. But, just as the first vaccine was revolutionary, and the iron lung saved many and targeted chemotherapy was developed, so will this generation’s toughest bugs be met with a host of ideas and possibilities.

Q&A with Dr. Margaret Wang, Pediatrician at the University Hospital

Q: What disease is most prevalent in today’s teen generation?

A: Influenza, infectious mononucleosis, strep throat and the common cold. The common cold is the most prevalent of all of those.

Q: What is an exciting technology in the field of medicine today?

A: What I think is a very exciting new technology [is] in the field of medicine and education together. A rare disease called eosinophilic esophagitis where

a patient has severe food allergy, sometimes to every food under the sun. These disease and no vaccine is 100 percent sure to prevent a disease, but they decrease

the likelihood. Patients can even die if they’re exposed to foods they’re allergic to. So a very wonderful technology has been developed where a student can stay at home but have a robot going to school. And the student’s face is on that robot in the screen and the student is looking at a computer at home and interacting with the teacher and all the students at school, but the student is at home, safe, but getting to socialize.

Q: What are some important habits teens can establish to lead healthier lives?

A: It’s a very common sense answer, but very true from a medical perspective. Get some sort of exercise every day, something to get the heart rate up, eat more vegetables and fruits, eat less fatty foods and junk foods, don’t smoke, don’t take illicit drugs and don’t drink alcohol.

By Ipsa Chaudhary

[/tab][tab title=”Revolution”]

[heading style=”1″]A new brand of #Revolution[/heading]

More than 400 protesters in Cairo, Egypt danced in front of the Muslim Brotherhood’s headquarters as an act of dance-driven defiance.

The videos, which usually last less than 30 seconds, include both masked and unmasked protesters wildly dancing to Spanish lyrics that translate to “Hey, shake, hey, shake. …. Shake with the terrorists. Hey with the terrorists. Hey, hey.”

The dance mob chanted “Leave, Leave!” at their president, Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first freely elected president, after the toppling of former president Hosni Mubarak. Recently, U.S. Secretary of State, John Kerry gave Morsi $250 million in American aid with the promise of democratic political and economic reforms in Egypt.

But the youth have not been satisfied with the progress. Many find it slow and consequently want him out of office. However, their words aren’t said across the press conference tables of Kerry and Morsi. They’re unleashed in the 140 character world of Twitter.

When ousting Mubarak, ‘#Egypt’ was the most popular hashtag on Twitter in 2011, according to Twitter’s “A Year in Review.” Also, “Cairo” was the most mentioned city that same year on Twitter.

On Jan. 25, the Egyptian government shut down most cell phones and Internet services, essentially stopping any form of telecommunications between protesters. According to the New York Times, 28 million Vodaphone subscribers in Egypt were without any cellphone abilities, and the company released a statement saying they “were obliged to comply” with the order issued by the government, all as a consequence of their protest.

Senior Mackoy Staloch is glad to see citizens of Middle Eastern countries advocate for themselves and for freedom, but he said the government is right not to underestimate the power of online protest communication. Like Egypt’s previous revolution, which resulted in Mubarak’s ejection from his position, Staloch worries the disorganization of the fight will ultimately pose difficulties for the revolutionists in coming years.

“The Arab Spring … seemed to be very disorganized forms of protest and revolt, so it was very difficult to come away with a single idea that both of those groups were fighting for,” Staloch said. “It seemed to be that there we just a lot of people fighting against something, not necessarily agreeing with each other over how to solve the problem they were fighting against.”

Such disorganization with modern protests is a problem not only in the Middle East, but also internationally. Occupy Wall Street, a movement which started Sept. 25, 2008, gathered a huge following. The majority of the protestors were young; the average age of an occupier was 33. They directed their “We are the 99%” mantra at bankers, other established financial corporations like Wall Street and the rich in the United States of America.

Here, too, the demands varied, and so did solutions.

Junior Pen Terry said these protests would have faded earlier had it not been for the media frenzy surrounding them, including television and social media attention.

“Modern protests are much more visible to the world than protests from the past,” Terry said. “In the past few protests had to be covered by news, and if they weren’t no one would know about them.”

The media, Terry said, are good at branding protests. Choosing buzzwords like “A mosque at Ground Zero.” Or “Freedom or death.” Or the oldest recorded telecommunication-started protest, “Go to ESPA. Wear blck,” where thousands of protesters in Thailand wearing black ripped up their ballots in 2006.

But like most things with the media, protests become “old news,” and soon people forget about them. After the hashtag stops trending, after the Facebook feed updates, after the news stops giving them airtime, suddenly the protest is finished and the change people around the world have been asking for must fill the void left from the aftermath.

“I would say Occupy Wall Street is dead for the most part. The reason I say this is because I can’t remember the last time I’ve heard it mentioned in any sort of media,” Staloch said. “But I don’t think they made much change. They were a huge movement, but in time they were forgotten.”

This generation’s brand of revolution, Staloch said, is different. Any movement — even the Harlem Shake — can quickly grab the attention of the world. Unfortunately, this does not always mean change happens, and even if change does occur, it is not always for the better in certain situations.

“I’m glad that Arab nations are overthrowing oppressive leaders,” Terry said. “They need to make sure that they are moving to a better government, not just replacing one bad leader with another.”

By Maria Kalaitzandonakes

Additional reporting by Hagar Gov-Ari

[/tab][tab title=”Memories”]

[heading style=”1″]Muting the scream: Science unearths potential to delete memories[/heading]

He would physically hurt her. He would tell her she was worthless and fat, that she would never amount to anything. At one point, his malicious words took poisonous root in her mind, and she believed the things he said about her as if they were the truth. Slowly, he robbed her of all the things she should’ve been able to carry as shields through adolescence: confidence, happiness, self-worth.

Now, several police and hospital-filled years later, Anderson’s life has never managed to recover from the beating it took so long ago. It still seems like the things he took away from her he took away for good. She is traumatized and has been so for the last several years of her life.

Some days, she wonders how beautifully different her life would be if she could simply wipe the memory away.

Though it may seem far more like a work of science fiction than truth, researchers around the world are working towards this precisely: deleting memories.

In a study conducted by the SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, for example, scientists put rats in a chamber. Stepping on certain parts of the chamber gave the rats a mild shock, and they quickly learned how to move around the chamber without getting shocked. Months later, the rats still remembered the safe path around the chamber; it had become a “long-term” memory.

But, when the scientists administered the drug ZIP, the rats immediately forgot the path. Essentially, the memory no longer existed. When testing was done weeks later to trigger the memories, nothing happened. The drug wasn’t wearing off, and the memories weren’t coming back.

“I was extremely happy,” neuroscientist Todd Sacktor, who leads the research team at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center, said. “The implications were that we had taken the first step to understanding long-term memory storage — and it looked like we were on the right path.”

Right now, the technology is in its early stages, only being tested on rats. But the implications of this technology for humans are staggering. It could smooth traumatic memories from the mind as if they never happened and with them, erase the emotional responses triggered by them.

For Anderson, it would mean a wholly different life.

“I feel like I’d be a lot happier; that’s the biggest thing — I’d be happier,” Anderson said. “I feel like I’d be able to not really care what people said about me cause I get really upset by things other people say. And then confidence, that’s a huge thing. Just that one memory, if it was gone, would change my whole entire life.”

People such as Anderson will be among the primary beneficiaries of this technology. The ability to delete memories would be a powerful attack against the debilitating condition of trauma, according to Sacktor. Long-term trauma, a prolonged emotional response to a severely horrific event, can ruin lives and relationships, and many never recover from it.

The technology could be miraculous, helping not only people with trauma, but also those who live with addiction or motor memory disorders. But, even if the battle of completing and perfecting the drug for human use is won, an equally large, less-easily won battle lies intimidatingly ahead of it: the battle of ethics.

With every leap of technology comes the same dogged question: is it morally OK? And when it’s the murky, uncertain field of memories that’s being meddled with, the stakes are high and the question pressing. Though it’s a question with seemingly no answer — whether humans have the right to tamper with their memories — Sacktor believes the potential benefits are worth the ethical consequences.

“I am a neurologist, a medical doctor,” Sacktor said. “Like any potential treatment, there is potential harm. Too much of many drugs can kill you. The point is to help people who are in severe distress — in a controlled manner by a professional.”

Though Sacktor and other scientists are pursuing their research in the hopes of changing lives, ethics are the reason Anderson wouldn’t delete her memories.

The effects of Anderson’s trauma linger unhappily. She’s still scared of relationships. She still hasn’t regained a sense of happiness and confidence. Last year, she was in the hospital because of a suicide attempt. But she said things are getting better. She feels she is growing as a person, growing back into life, and that wouldn’t be true without the memory.

“If you have these bad memories, you’re supposed to learn from them,” Anderson said. “Without them you wouldn’t learn; the same thing might happen again, and you’re gonna get that memory removed again. And it might just become a cycle, and you don’t want that to happen. I want to say I would do it, but I feel like what happened has made me a stronger person, maybe not the best person, but a stronger person. It has messed me up a little, but in the end, it’s going to be OK.

I really hope it’s going to be OK, and I think it will be … little things are going to happen that’ll slowly push back that awful memory. And I’ll grow for the better.”

*name changed upon request

By Urmila Kutikkad

[/tab][tab title=”Designer Genes”]

[heading style=”1″]Controversy clothes designer genes[/heading]

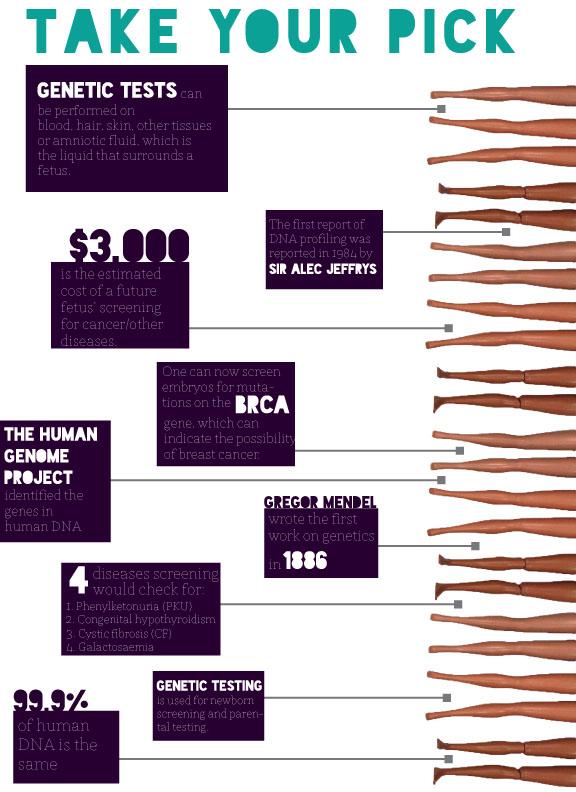

In May of 2008, Yale University researchers published their findings of successful genetic engineering on mice bred to have dementia-like symptoms. They found that by using genetic engineering to block a part of the mice’s immune systems, it resulted in defense cells, known as macrophages, which got rid of the plaques causing dementia.

Genetic testing lays the foundation for future genetic engineering by bringing up prevention of disorders, said Christine Roberson, the Laboratory Technology instructor at the Columbia Area Career Center. But she noted current genetic engineering is most commonly used in modifying feed crops, engineering human insulin, human growth hormone, proteins and other pharmaceuticals used in vaccines.

Crops, such as BT corn and Roundup Ready soybeans, contain genetically engineered DNA. In addition, scientists are attempting to engineer a vaccine that will be more effective for the flu so that individuals would only have to get the vaccine every two or three years, Roberson said.

“If we’re talking about making pharmaceuticals, making vaccines, engineering crops, we’ve progressed pretty far,” Roberson said. “A lot of our medicines right now are genetically engineered. … Diabetes is a huge example. The insulin that people use now is human insulin that was genetically engineered. The human gene [is] put into a bacteria, and it produces the human protein for us.”

The theory behind prevention is genetically modifying or engineering the DNA so that it no longer contains the mutated genes. The potential technology when implemented in humans, though, brings with it a complicated moral debate for some.

“I mean, if there weren’t any risks involved [in gene modification], then I would say, ‘Why not?’” Rohrer said, “because we’re not really a religious based family, so that wouldn’t be a huge problem.”

However, not everyone sees the issue so simply. According to ethics.missouri.edu, arguments against genetic engineering include ideas that it is “unnatural, dehumanizing, that it will result in obsolescence and that it is a version of eugenics.” Many oppose the technology on a religious basis. In March of 2008, Pope Benedict, for example, released a list of seven new deadly sins, one of which was genetic engineering.

Though junior Inas Syed considers herself religious, she said the reducing of an individual’s lifelong suffering outweighs genetic engineering’s questionability. She doesn’t think genetic engineering in medical cases is going against God’s will.

“Maybe God wanted us to have this technology to change the quality of life,” Syed said. “I think God put the technology on Earth or gave people the intelligence to make that technology to advance.”

Although for many the issue of genetic engineering has become a religious one, it goes beyond that for Roberson. Sickle cell anemia is a recessive gene that affects those who inherit the gene from both parents. This results in a shortened and painful life, Roberson said; however, according to sickle.bwh.harvard.edu, individuals who are merely carriers of a sickle cell anemia, meaning they only have one of the recessive genes, are more likely to survive malaria. In addition, scientists speculate that carriers of cystic fibrosis are more likely to survive cholera. So now, scientists are uncovering the benefits of genes that 50 years ago, society would’ve completely wanted to eliminate from the population, Roberson said.

“I always tell my students the reason that I’m here rather than in Ireland is because Ireland had no diversity in its potato products, and it wiped out all of the potatoes in Ireland in the 1840s,” Roberson said. “So if we engineer humans and change it in such a way that the children are also engineered, we lose a huge piece of diversity in the human population, and that’s just not wise in terms of evolution.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, genetic tests have been developed for more than 2,000 diseases. They are able to diagnose a wide variety of disorders from Fragile X Syndrome and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy to even testing for ovarian and breast cancer.

In October of 2012, researchers led by Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a reproductive and developmental biologist at Oregon Health & Science University in Beaverton, demonstrated that a genetically engineered technique works to prevent mitochondrial disease in rhesus monkeys. Additionally, a St. Louis based company, Sigma-Aldrich, has a product known as Zinc Fingers that would allow scientists to cut off a specific set of base pairs from human DNA. This would result in the prevention of disease like sickle cell anemia, Roberson said.

Roberson said Zinc Fingers are “kind of far future. The mitochondrial stuff, they’re getting ready to start human trials now. In terms of offspring, doing Z Fingers, cutting out and replacing is much farther down the line, but it is a possibility.”

The future of genetic engineering may still be unclear; however, there are several methods scientists are currently exploring to stop the transmission of hereditary diseases. For example, Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis, also known as Preimplantation Genetic Testing, has become an alternative for other invasive genetic testing. According to the American Pregnancy Association, the PGD procedure starts with in vitro fertilization. After the embryo divides into eight cells, scientists retrieve the DNA from a few of the cells and copy it through a process known as polymerase chain reaction. Then, using molecular analysis, they evaluate the DNA to determine whether or not the embryo would have the diseased gene.

Though she doesn’t think genetically engineered children would be wise for the population, Roberson can see the possibility on the horizon. Both Rohrer and Syed agree, saying if genetic engineering is plausible and would increase the quality of life, then there is nothing wrong with it.

Roberson, however, isn’t so sure.

“We’re going to watch the film Gattaca, which is all about genetic engineering and design,” Roberson said. “I hope [genetic engineering] doesn’t go to that point because I think we start losing our human uniqueness. If everyone is engineered to the same specification, then no one is unique, and an important part of humanity is that we are unique and I’d hate to see us lose that. Unfortunately, based on what we do with things like plastic surgery, I’m not sure we won’t go down that path. I hope not, but if I came back 200 years from now, I guess it wouldn’t surprise me.”

By Trisha Chaudhary

[/tab][tab title=”Body”]

[heading style=”1″]Innovations, nobody excepted[/heading]

This machine, more commonly known as a 3-D printer, layers threads of ABS plastic to turn computer models into physical objects. Allee also used the grant money to purchase a mill and a lay to show CAD students the contrasts between the two manufacturing processes.

“An ABS printer takes from nothing and builds up, whereas a mill and a lay take from a solid object and cut away. So [the 3-D printer is] a reverse of what we’ve always done in the past,” Allee said. “When we wanted to make a part in the old days, we would actually have to take and put a piece of metal in, we’d have to take drills and grinders and in-mills to cut away, carve away, the surface, whereas the 3-D printer allows us to do the reverse of that. We start with nothing, and we spray the solid.”

From an educator’s perspective, the 3-D printer lets learning happen on a much quicker scale, Allee said. If a model isn’t working correctly or if parts do not fit together exactly, the 3-D printer allows students to adjust the measurements and sizing on the computer before printing out another prototype. It’s much more economical, both in terms of money and time. Within a day or two, depending on the size of the error and the project itself, students can have a new prototype ready to retest, without remaking a mold or redesigning. The 3-D printer gives students the opportunity to see “real-life” applications of what they learn.

“You can physically grab something that was a 3-D model on your screen, and you bring it to life,” Allee said. “That’s insane, you know? That’s ‘wow.’”

For junior Jonah Smith, who is in his second year of the CAD program at the CACC, the feeling of grasping in his hands what had only previously existed on a computer screen is the most rewarding feeling. With sculpting, mistakes like “accidentally scraping off a piece you need” can mess up an entire project, but the 3-D printer provides the extra precaution of laying down support material to keep everything “contained.” Once a student has designed their model, the only setbacks he or she can face is if the printer runs out of material, Smith said, but that only requires him to replace it with a new cartridge.

“When you get back into the classroom and you find the piece there, it’s not just the piece. There’s support material around it also that you have to take off, so [that unveiling] is kind of cool,” Smith said. “The feeling that you get from making the actual object is better than just going out and getting it, because you know that it’s your creation.”

Beyond the pride that comes with self-sufficiency, the 3-D printer may also change America’s “throwaway society,” said Craig Adams, CACC instructor and district practical arts coordinator. The printer has already reduced his reliance on buying new items to replace lost or damaged ones. When his kids’ play tent had a broken part that prevented its use, Adams made the missing piece himself in the 3-D printer. Without the wait of searching, ordering and shipping an entire new tent, Adams made the existing set usable again.

It’s “planned obsolescence, like a light bulb,” Adams said. “We design things so that they will break down, and we have to go and purchase new ones. Otherwise we don’t have that exchange of goods and services. Well if I can go out and replace a plastic part, … if I can design it myself, then I’m not spending [that money].”

The technology of the 3-D printer especially appeals to those in the ‘Maker Movement,’ he said, who have also worked to reduce costs of the printer itself. The most basic 3-D printers are now available for a few hundred dollars instead of several thousand. But doling out the latter cost will pay for a more sophisticated printer that could, for example, print objects within other objects, Allee said, such as a heart with the valves inside. The CAD printer, by comparison, could only produce such a product if each half of the heart was printed separately, he said.

While the cost of 3-D printers has dropped significantly, the range of types and models has increased — for just more than $4,300, one can purchase the Choc Creator V1, the world’s first 3-D chocolate printer.

Adams hopes to expand the customer base of the 3-D printers by getting other teachers involved. A series of classes, called Project Lead the Way, focus on preparing students from grades six to 12 for the engineering field using 3-D printer technology. Adams believes the printers can help others outside of the traditional ‘industry’ subjects, though, including art teachers.

As users increase, the potential dangers of misuse similarly escalate. No one would spend $18,000 to design and print out a plastic gun, Allee said, but the likelihood of this occurrence increases as prices decrease. But fear of mishandling and abuse, Adams said, should not prevent the further development of 3-D printers.

“There’s misuses for a lot of different things, but that doesn’t mean you stop progress [or] you stop technology,” Adams said. “That just means you look at how you, you know, let’s say, the way you search people on the airplane or you change the way you’re securing a school.”

By Nomin-Erdene Jagdagdorj

[/tab][tab title=”Lies”]

[heading style=”1″]Week of Honesty challenges communication[/heading]

The concept was simple: one week, no lies. A social experiment to experience life as if honesty were the only option. According to webmd.com, Americans tell an average of 11 lies per week, so that was roughly 11 instances of dishonesty that I would have to avoid. And although I would not consider myself to be a profoundly dishonest person to any degree, I knew the little white lies that weave their way into daily conversation were going to be difficult to disembed from my routine. This ongoing struggle to avoid the minor instances of dishonesty, combined with the horrifying news which had just graced the screen of my cell phone, left me wondering how I would possibly stay true to my oath of truth.

I soon realized planning a surprise party cannot be done in a legitimately honest manner. As I slid nervously into the drivers seat of my car during lunch that same day with the birthday girl in the passenger seat next to me, I was praying she didn’t hold any suspicions. But the first words out of her mouth were “My mom is acting suspicious. I think she’s planning me a surprise party.”

I froze behind the wheel, torn between upholding my “no lie” policy or ensuring the secrecy of the exciting news with which I had been entrusted. I laughed nervously, trying to brush it off and quickly assured her, “She would definitely tell me if she was planning one.”

Technically, this wasn’t a lie. She would tell me. She did tell me. But if I left that part out, telling only half the truth, I was still being honest, right?

As much as I tried to dance around the truth and be honest, yet misleading, the true spirit of honesty – “the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth” – was not upheld in my friend’s party planning process.

I’m not proud to say this wasn’t my only slip-up during my seven days of alleged honesty. Small lies slipped out of my mouth before I even realized I wasn’t saying the truth — which isn’t a surprise as 60% of people will lie at least once during a ten minute conversation, according to statisticbrain.com. Out of habit, I found myself making up vague excuses for why I couldn’t hang out with someone, when in reality, my only prior engagements involved sweatpants and a never ending Netflix marathon. I promised my sister I didn’t steal her headphones and swore to my dad I would stop using his credit card at Panera.

But despite these habitual lies that graced my daily conversations, the times when I stopped to re-evaluate my knee-jerk white lies proved to me the most rewarding moments of the week. I realized that many of these little lies have no real grounds of validity. I came to the conclusion that it’s not necessary to pretend I’m grounded when I could just as easily say, “Hey, I like hanging out and all, but I’ve got a date with my couch I can’t miss,” or tell my dad that the truth is, I can’t be trusted with his Mastercard when the alluring scent of gooey butter pastries and steaming broccoli cheddar soup is impairing my mindful judgement.

As daunting as the task may seem, telling the truth can provide benefits beyond the warm and fuzzy feeling of sincerity. In fact, in a recent experiment, researchers found that avoiding lies can actually improve one’s health.

At the 2012 meeting of the American Psychological association, Anita Kelly, a psychology professor at the University of Notre Dame, presented the findings of a study which monitored the health of 110 individuals over the course of 10 weeks.

One group was given directions to go about life as usual while the other group was told to only tell the truth. The findings concluded that participants in the “no lie” group, who told three fewer minor lies than they did in other weeks, had four fewer mental health complaints and three fewer physical complaints after the study concluded.

Although it might feel like dishonesty is a necessary evil in the game of life, practicing integrity on a regular basis will ultimately leave you more satisfied and able to navigate nearly any situation in a sincere and genuine manner. And that’s no lie.

By Anna Wright

[/tab][tab title=”Columbia”]

[heading style=”1″]Skylines, farms and ancestry[/heading]

Among neighboring mid-Missouri towns, Columbia is wildly successful, known among some as ‘The Bubble,’ and has ranked as high as second place in Money Magazine’s list of best places to live.

It’s a phenomenon that first appeared when manufacturing and farming jobs began to shrink in the mid-twentieth century, and the communities around mid-Missouri began to wane along with them. As the economy ebbed and flowed, so did the fortunes of communities dependent on the price of grain.

Deborah McDonough, Advanced Placement Literature and AP Language teacher, grew up in the farming community of Marshall, Mo. Towns like her hometown were hit hard while Columbia’s growth remained steady, and she was shocked when she returned in the mid 2000s.

“When you talk about economic hard times, farmers have had a huge problem. And also, [Marshall] used to be a meat-packing area, and it used to be a shoe factory, a famous shoe factory there. And because of the economy, a lot of those places closed down — people lost their jobs, a lot of people lost their land. And these were generational farmers,” McDonough said. “I think a lot of the reason Columbia survived is [because of] their infrastructure. They have State Farm. They have the University of Missouri-Columbia, and they have a renowned medical institution here. And those three things coming together in one place made it pretty solid.”

Weathering the storm for Columbia was Hindman, a former mayor, lawyer and invested citizen who was approached in 1995 about running for the office. He was elected for five consecutive terms before stepping down in 2010.

Although probably best remembered for his devotion to building trails and parks — a policy of one within a quarter mile of every housing development, he said — he also oversaw the end of a period of explosive prosperity and the rocky aftermath of the 2008 national economic collapse. He said that the engine of change was a string of successes in education and an enormous internal drive toward population growth.

“People want to live here; they want to stay here. They want to raise their families here. A surprising amount of the increase in population is from people establishing families here and having kids; and then their parents move in here,” Hindman said. “And Columbia gets great ratings as a place to do business, as a place to retire, as a place to live and as a place to raise a family. And all those things bring people.”

As the steward of the new houses, eateries and icons of Columbia’s culture — Ragtag Cinema opened in 1999 in Hindman’s first term as mayor — Hindman said the challenge of the time was balancing the needs of growth with Columbia’s famous small town aesthetic. Developers were incredibly aggressive during the housing bubble of the mid-2000s, he said, and the city government had to fight both development and anti-development interests in an effort to find an equilibrium that he believed would be best for the citizenry.

“I was very anxious to see Columbia be the best place to live. My theory of what I tried to do as mayor was to try and make, from a civic point of view, a community that would provide as many people as possible with satisfactory lives, and I felt that such things as choices in recreation and transportation were really important to that goal,” Hindman said. “But I of course still worked on such types of things as streets and economic development and airports, the many many things you have to do as a city – the police, the public safety, police and fire. We built several fire stations, added a significant number of police officers. Actually, I think while I was mayor we put the first set of computers in the police cars.”

As to the future, Hindman and McDonough agree that expansion is inevitable, though McDonough believes it won’t occur at pre-recession levels. Hindman thinks there could be rocks in the road if MU begins to struggle, but he believes that it is the destiny of Columbia to continue development. The role of city government, he said, will be in curating that advance.

“You just try and leave your city the same, and you know it won’t be the same – no human endeavour is ever completely static – and so Columbia is going to change,” Hindman said. “Even if you didn’t want it to grow it’s going to grow.”

By Adam Schoelz

[/tab][tab title=”Music”]

[heading style=”1″]Fiction: The day the music died[/heading]

He’s never looked quite so lost. His fingers linger above the white keys; hovering, suspended. But he doesn’t dare touch the ivory. He knows nothing will happen if he does.

“So, should I just drop dead now?” he asks, his eyes not leaving the piano. “Or what?”

Elisa says nothing. There’s nothing she can say.

Silence squeezes everything together. Elisa and Rick are in a completely empty room, just the two of them. To Elisa, it feels claustrophobic. Everything feelsclaustrophobic these days. The world is hushed. People are afraid to speak. It’s noise, and noise reminds them of music.

It’s quiet between them for a few minutes. Rick continues to blink at the keys, as if just staring at them will make them produce sound.

“I keep thinking it’ll just come back,” he says, “that suddenly I’ll be able to hear and play music again, and we’ll be back in the choir room, and there will be dance parties again, and the drums won’t sound so dead, and the room won’t be so empty.”

“And maybe the newscasters will actually give us a new story,” Elisa replies.

This, of course, is something of a joke, an attempt to lighten his mood. She’s checked every journalism website every day for the past three weeks, but the headlines are always similar. They always point to the same problem: humans are missing something they’ve had since the beginning of time. “Scientists Continue to Investigate Lost Music,” the papers say. “Musicians Search For New Career Path.” “Student Files Lawsuit Against Record Company for Selling Fraud CDs Titled ‘The Last Music On Earth.’”

It’s all a bunch of talk about nothing. No one has any idea why, all at once, music disappeared from the world. It was there one moment then gone the next.

Elisa remembers because she was singing when it happened. She was pacing about her room, clutching a pamphlet of sheet music. She was slapping her hand against her thigh (one-ee-and-a-two-ee-and-a-three-ee) thinking there was no way she would be able to hit a high C without cracking when her voice disappeared. Her lungs were still heaving air; her vocal chords were still working, but there was nothing she could hear.

Terrified, she rushed to the bathroom and guzzled water, lozenges, herbal tea. She could speak completely naturally. But her singing voice was gone.

Then she found iPhones didn’t play iTunes anymore. Instruments wouldn’t make a peep. Stereos only projected speaking, monotone voices.

The world was suddenly and intensely quiet.

Now, three weeks later, the whole world has changed. Or, at least, Elisa’s has. She’s always been a relatively happy person, but these days she’s sneaking her mother’s Lunesta just to get to sleep at night. Her choir rehearsals have all wound to a complete stop. She can’t play her “homework playlist” while she studies anymore. She’s never once gotten a traffic ticket, but now she’s having difficulty paying attention to other cars; she can’t focus without the radio playing.

But she supposes she doesn’t have it as bad as the others — not as bad as Rick. Rick was planning on making a career of music. He wanted to be a big-time studio recorder, playing whatever instrument he could get his hands on. He wanted to tour. He wanted to be with the “music scene,” wherever it was and wherever it went.

But there’s no “music scene” anymore. There’s not even a cassette tape from here to Acapulco that works properly.

What do you do when something you’ve chased after your entire life is pulled out of existence?

Rick interrupts Elisa’s thoughts, speaking for the first time in a while.

“I’m sorry I never finished any music,” he says. “I’m sorry I never wrote you a song.”

“Rick, I —”

“No. Really.” He looks up at her, his face grim. “I’m sorry. If I could write you one now, I would. I would spend as much time as it takes.”

“You were busy, with your life at home and your college auditions —”

“Those don’t matter much now, do they?” He kind of smirks. “College auditions. I won’t be going to college for music now, will I? I don’t know what the hell I’m going to do with the rest of my life.”

“You don’t know it won’t come back.”

“What, music?” He laughs, but it’s a cold and dark laugh and one that Elisa immediately hates. “I really hope it does. But I’m not keeping my fingers crossed. I’ve tried everything, Lis; I’ve tried to compose with just ink and paper but no sound, no music. I tried to strum my dad’s guitar until my fingers were bleeding.”

“Everyone’s tried that, Rick. That doesn’t mean we should just give up.”

He sighs. “I know, Lis. I know. But people get tired, when they keep doing the same thing over and over again with the same disappointing result. They get really tired.”

“It’s only been three weeks.”

“Three weeks is enough for me,” Rick says, slinging his bag over his shoulder and heading for the door. “It’s enough.”

***

Elisa doesn’t speak to Rick for almost a week. It’s terrible, watching him walk through the halls with his headphones in, pretending he can hear music when he can’t. He avoids eye contact and sleeps through the school day. Elisa figures he isn’t getting much rest at home.

As for herself, home life isn’t so peachy either. Her father gets home late every night, trying to keep his radio station running. Her mother tries picking up extra work as a waitress, but it isn’t easy to live off of tips. Elisa spends most of her after school time at the retirement home with her grandmother, who’s almost completely deaf.

Every once in a while, her grandmother asks for music. She asks for Elisa to turn on a record and, since she’s deaf, Elisa doesn’t think it matters anyway. Her grandmother has no idea that music is gone because she can’t hear it. So Elisa pops a CD into the stereo, even though no voice will begin to sing and no band will start to play.

That’s when she gets the idea. It hits her like cold wind, overpowering everything else in her mind. She’s turning on the stereo, when it just hits her.

Deaf people don’t hear music. They feel it.

She calls Rick the moment she gets out of the hospital.

“Hello?”

“Rick! You know how deaf people obviously can’t hear music, right?”

Rick is silent for a moment. “Elisa? What are you talking about?”

“But when they feel the vibrations through the air, it’s almost like hearing the actual song,” Elisa continues, disregarding his question. “They can almost hear it in their minds.”

“What are you saying?”

Elisa grins. “I have a plan. I say we host a concert. We get the best musicians in town, all in one place. They play the world’s most well-known songs. They play the ‘Star-Spangled Banner’ and ‘Billie Jean’ and ‘Bohemian Rhapsody.’ We get huge speakers, and send out amplifications — vibrations — like you would feel as a deaf person. Then…it should almost be like actually hearing the music. We already know what it sounds like. It’s already in our heads.” She paused for a moment, her excitement palpable. “What do you think?”

She waits for Rick to consider. There’s at least a full minute when all she can hear is the sound of his breathing. Then:

“Yeah. Yeah, I think it could work.”

***

When ‘Hotel California’ comes on, Rick starts to cry.

He doesn’t let anyone see it. They wouldn’t see it anyway; the room is dark, illuminated only by the giant stage lights. But he’s crying, and he isn’t ashamed.

He can hear it again. Maybe not literally. But there is a band on the stage, and they’re slamming sticks against drums, they’re stroking guitar strings, they’re doing everything that would normally be done to play music. There’s a huge projector screen above the band, displaying the lyrics: “Welcome to the Hotel California. Such a lovely place, such a lovely face.”

And Rick can hear it. Rick can hear it as he used to, when he was only a couple feet tall and his mother would dance with him in the kitchen. It would be dark outside and Dad would be on his way home from the office. Mom would turn on The Eagles and swoop Rick into her arms, singing softly into his ear and slow-dancing across the floor.

The vibrations of the speakers thrum throughout the auditorium, sending odd shivers across his body, but Rick welcomes them. He welcomes the unnerving feeling, because it’s like hearing Don Henley sing, “but you just can’t kill the beast!”

It’s working. Elisa’s crazy plan is working. He has to find her.

So he starts running. He discovers her backstage, giving a couple of bottled waters to exhausted performers.

“Elisa!” he exclaims. “I was looking for you.”

“Sorry, Rick, I’m a little busy —”

“Stop for just two seconds. I’ll take those.” He grabs the Evian from her arms and passes her something else.

She raises an eyebrow, then looks down at the item in her hands. It’s a pamphlet of hand-written sheet music. Scribbled across the front is: “To Elisa, From Rick.”

The song has no title, but it begins in 4:4 and ends in 7:8. It’s chock full of accidentals, and goes through four different key signatures. It’s outrageous.

“I wrote a song for you,” Rick said. “Finally. I know you can’t hear it, and perhaps you won’t ever be able to, but I did it anyway. I’ll play it for you sometime.”

Elisa stares at the pages of ink for several long moments, examining the way Rick had crossed out certain notes and replaced it with others.

She takes a deep breath, and says, “Play it now.”

Rick looks confused. “Huh?”

“Get out there, and play it now. Play it before the entire audience at this concert. It’ll be your first live performance, your debut as an artist.”

“Elisa, you’ve got to be kidding me. They won’t even hear it. Not really. And, anyway, I’ve never even —”

“Rick, just because the music is ‘gone’,” she signs quotation marks with her fingers, “doesn’t mean you weren’t always meant to be a musician. That’s who you are.

So get out there and play the song. It doesn’t matter if they won’t really hear it. They’ll feel it.”

“Lis, I —”

Elisa cuts him off. “You ever wonder how many people have been ready to kill themselves, ready to give up on the person they love, ready to submit to the depths of depression? And then they hear the perfect song on the radio. They hear some stranger’s voice telling them it’s going to be okay, and suddenly it is.” Rick blinks at her, reduced to silence.

“Music expresses what verbal communication can’t,” she says. “It’s raw feeling. The world was given music because it’s one of the only ways to properly communicate emotion.” She smiles at him. It’s a sweet, encouraging smile, one of those smiles that would stick in Rick’s memory for years.

“So, for God’s sake, Rick,” she says. “Go play my song.”

By Lauren Puckett

[/tab][tab title=”Anonymous”]

[heading style=”1″]Internet culture allows for anonymity[/heading]

It beckons the mind to wonder what would occur and what wouldn’t if anonymity had never existed online. Both its repercussions and benefits would, in a way, correlate. All completely intertwined, one domino knocking over the next, in a stupid analogical kind of way.

To start things off, I would like to bring to attention that the use of anonymity has been present long before the Internet became a factor in any of this at all. Animals have used disguises for thousands of years; it’s in their genes. How does a chameleon survive in the desert? Why are insects skin patterns similar to those of their habitats? The answer is clear: camouflage, disguise, anonymity.

Anonymity appears in every aspect of existence and probably beyond that, ruling over all entities supremely. The nonexistence of it is simply unfathomable, especially in the age of the Internet. And even if somehow the human race was able to form in such a polar opposite of a universe, the moral compass of the entire species would be completely foreign to that of our shrouded and obscure philosophies. I say this after seeing dozens of scientific studies showing that most humans’ dishonest behavior occurs in situations where people are allowed anonymity. For example, University of British Columbia researchers found that people are 31 percent more likely to lie over text than face-to-face.

Even major corporations have taken steps in discouraging such behavior. According to joint research done by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Southampton, “Influential Industry titans like Facebook argue that pseudonyms and multiple identities show a ‘lack of integrity.’” They also went on to say that “removing traditional social cues can make communication impersonal and cold,” helping to reiterate the point that anonymity only leads to the undermining of not only general social skills, but also credibility in many cases.

According to another paper written by researchers at both Rutgers and Texas University, studies have shown a direct correlation between anonymity and group norm violations, socially crippling future generations.

Think about the Internet without anonymity. What would the Internet look like if, upon logging onto the World Wide Web, you needed to enter your social security number or scan a QR code? What if everything you did online had your name attached? Would Amazon’s shipping and buying services exist if people felt uncomfortable signing their names to negative comments? What would Twitter be like if both the tyrants and jesters had to come out of hiding? Would our political climate be any different if mudslinging and fact creating had names attached?

But what would be the price?

The Internet, in a way, is like being baby-sat by an irresponsible teenager: pretty much no rules and unlimited freedom. And when the “babysitter” sits in the corner preoccupied, some roughhousing gets missed. For some, the black hole that is the Internet acts as merely a medium for what some perceive as hate. Others, however, such as Anonymous, the infamous hacktivist group, utilize both the Internet and anonymity in their attempts at serving justice where it sees appropriate.

Emerging from the depths of the Internet in early 2003, Anonymous serves as a way for all (due to the loose association of the term) to unite under circumstances of cloak and dagger and serve a harsh and swift punishment to those it feels deserve it. Time Magazine elongated its merit and named it one of the most influential groups ever, all underneath a disguise of fabricated profiles, stolen passwords and other means of Internet-ing, making Internet guerrilla warfare a refined and stealthy art. It simultaneously reiterates my point that anonymity is crucial to the structure of what we believe to be anything, and that justice somehow comes about through anonymity.

And not only that, it protects our pride (so that John can fart while walking down the street and avoid the blame), it protects our safety (that way after Sal says, “police officers are stupid pigs,” they can’t come hunt him down) and it allows forums such as Tumblr, Wikipedia and political chat rooms to exist.

On a final note, in future endeavors regarding the world in general and it’s plethora of faceless cynics, keep in mind that they are merely taking advantage of it’s existence, simply utilizing a privilege that (insert deity here) has deemed the human race responsible enough to handle.

By George Sarafianos

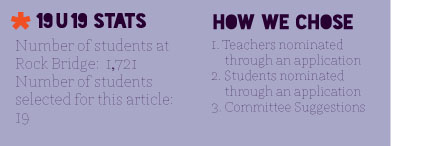

[/tab][tab title=”19 under 19″]

[heading style=”1″]The up and coming[/heading]

Mariam Yahya (18): Proponent for ELL

“I use my own experience to help them,” Yahya said. “It’s easier to communicate with ELL students after you’ve done it yourself.”

That form of communication is something Yahya calls “Special English,” a mixture of simple words, hand gestures, facial expressions and a whole lot of love, she said. Yahya uses this talent of communication in her work in the RBHS English Immersion Center, where she tutors level one students on simple words and conversations.

“I try to use what worked for me – I pull up Google images of a word to show them what it means. I give them lots of examples, and I just go slow,” Yahya said. “I have fun, and they do, too. We’re not TA and student; we’re friends.”

Yahya’s work as Chief Refugee Crisis Officer takes her beyond the classroom. She visits students in the hospital, delivers them to their busses, meets with their parents to help them understand cultural norms, advocates for them in school transfers and works to support any students struggling to meet their basic needs. This year Yahya saw an ELL student board the bus without a jacket, though there was snow on the ground.

“When I saw her without a coat, I took it really seriously. I started a drive for hats and gloves and coats and things at Rock Bridge for the ELL program,” Yahya said. “We collected more than 10 boxes and gave them to the students that needed it.”

Yahya has found a community within the ELL classrooms, and she chalks it up to the teachers. ELL teachers, she said, are so much more than instructors; they care for their students in a whole different way, and now, after seeing the impact of these teachers, she said she wants to follow in their footsteps.

“What I’ve been through inspired me. My ELL teachers were everything to me, and they’re everything to the ELL students today,” Yahya said. “These teachers taught them, clothed them, shared breakfast with them and made them feel safe when their whole world was changing. … I want to become a teacher one day. What I saw was a different kind of teaching.”

Yahya taught the students about dressing up for their first Halloween and instructed them in how to cut a pumpkin’s eyes just right for a jack-o-lantern. She helped them apply for jobs and practice their interviewing skills. She showed them how to play Bingo and make a snowman. She is their advisor, teacher and jester.

“Look, everything I do in the class is to be a friend. … When I first came here I felt so isolated,” Yahya said. “But they don’t have to go through that. I will help them.”

By Maria Kalaitzandonakes

Michael Hawke (18): Orator

A: Debate is really a community activity. It’s not like other clubs where you’re friends with everybody and it’s great to see them on a Tuesday morning. I mean, when you are on the debate team you will see everyone’s greatest accomplishments and their greatest failures. … The level of trust you develop with that is huge. They basically are a surrogate family to you.

Q: What are your greatest debate accomplishments?

A: The first awards I won in debate were at the Parkway South Tournament last year when I won second place in novice extemporaneous speaking. The month after that, I competed at the Ladue Novice Invitational and won first place in the public forum novice division and second place in novice extemporaneous speaking. Later that year I won first place in novice public forum at the Jeff City tournament and second place in extemporaneous speaking at MSHAA Districts. This year I won sixth place in international extemporaneous speaking at the Jeff City tournament and 2nd place in international extemporaneous speaking at MSHAA Districts.

Q: What experiences have helped you advance in your aspirations?

A: There are a handful of universities that do summer debate programs. … The one I attended was the Harvard debate camp. … I went to Boston on my own for two weeks. … I basically just practiced debate skills.

By Ashleigh Atasoy

Chandler Randol (17): Teen suicide stopper

Because of these disturbing facts, junior Chandler Randol made suicide prevention more of a priority topic in Columbia Public Schools.

In his freshman government class, Randol participated in Project Citizen, a program for students to identify policy issues in the community and develop ways to take action against them. Randol and his group members were adamant about increasing the instruction time for CPS students concerning suicide and it’s prevention.

“We developed this project in class for basically the entire year,” Randol said. “There were many recent suicides at that time. … It’s sick when kids are, like, 12, and they want to kill themselves.”

The group researched modes of suicide prevention and current policies, while others wrote the new policy and discussed how to implement it. The current CPS policy only requires middle schools to talk about suicide once a year.

“We decided that wasn’t enough, and we wanted 450 minutes [a year] … set into place in sixth and eighth grade,” Randol said. “The policy we wanted to leave pretty simple. … We want to talk about all the different things, bullying, the side effects of bullying, going about what self-harm is and what that actually means.”

After coming up with this idea, the group worked toward perfecting the presentation they were showcasing at the upcoming Project Citizen competition. Randol worked closely with junior Haley Benson as this project progressed. After rounds of competition, Randol and Benson nervously awaited their results. At the end of the competition day, they weren’t disappointed.

“We ended up getting second place without any help from [our teacher], other than just motivating us,” Randol said. After competing, “we went and set up a meeting with [Superintendent Dr. Chris] Belcher to actually implement what we created into the school policy.”

Belcher reviewed their policy, which will go into effect next year. In addition to the implementation of the policy, Randol and Benson won the Missouri Suicide Prevention Project youth award for their efforts.

In the beginning, Randol wasn’t even sure that he wanted his project to be instituted — it was just a school project. However, he learned students can make a difference if they choose to take action.

“So many people are almost always complaining about what people aren’t doing, but you can actually go out and do it yourself,” Randol said. “It’s been really cool to promote this idea that we don’t have to look up to adults to do everything, if we’re mature enough we can actually make a difference in our community.”

By Brittany Cornelison

Ashley Rippeto (17): Shoeless Songbird

The next person to notice was Rippeto’s voice teacher, who admitted she didn’t need the lessons. Practice, stretching her vocals and learning more about her voice were her only suggestions for Rippeto.

Ever since she realized her talent, Rippeto noticed that singing allows a constant flow of interaction. The reactions in the audience give her a feeling of joy, she said. She sees every performance as an opportunity to meet new people.

Rippeto has been working with B.J. Davis, her producer, on her first CD for a year. It is a tedious process, and Rippeto said she deals with high expectations.

“People say that your first CD should be your best one, but I disagree. I think you learn from it,” Rippeto said. “The only song I really have right now is ‘Barefoot and Crazy,’ and it’s kind of like my logo song. … It just explains me. Barefoot and crazy, that’s what most people say about me, I love my family and I love my God, and I’m footloose and fancy free.”

The lyrics she sings define what is important to her. This song, available on her upcoming album, will be available on iTunes once it is released. Rippeto sings Christian and country music, and her lyrics define her personality. Rippeto also said being a singer requires her to create a trademark style, “like Nicki Minaj and her pink hair.” She has already thought of how to show off her own personality quirks.

“I love singing barefoot. … You can’t wear boots on stage because they’re too loud, … and I hate flats and any other kind of shoes,” Rippeto said. “I was at a show one time, and my mom made me wear these really stupid flats that I didn’t want to wear, so … I just kicked them off on stage and started singing barefoot.”

Rippeto won Mid-Missouri Idol, playing barefoot, in 2008. As she works on completing the CD, she keeps her spirits high for her future. With a little work on her stage skills and taking constructive criticism, she feels she could be a professional singer.

“I keep saying to myself that if I have faith, it’s going to happen. And I’d just like to sit here and watch it happen,” Rippeto said. “But I have a few more steps to take before I’m ready to get to that point.”

By Afsah Khan

Mahogany Thomas (17): Soul Barista

A: My favorite thing about my job is that I view it as a ministry. … Every day you come in contact with cancer patients. You come in contact with people that’ve just lost their leg. You come in contact with veterans. … You come in contact with people who just broke their backs. And they’re all down, and you have the ability to not just give them coffee — you have the ability to provide them with support.

Q: What’s your best “on the job” story?

A: I met a man about a year ago and he came up to me and said, “You just have the best smile, Mahogany. … My wife’s like that, too. She’s just really pretty, just like you, radiates personality … but she doesn’t think that now because she lost all her hair, and she’s wearing a wig.” And I said, “Oh, I’m really sorry, … but I’m sure she’s beautiful.”

Two days ago they came back to the hospital, and I was like, ‘You’re still beautiful as ever.” Because you remember these people, you remember who you interact with. You remember the people who you pray for, the people who you talk with. And just to see the smile on their face … makes such a difference.

Q: What is your life motto?

A: “Even a smile makes a difference.”

Q: Where do you find your strength?

A: You look at the … people who need you, and that’s where you find your strength because it’s the mother of a cancer patient who is with her son, day in and day out, and always has a smile on [her] face that makes you smile. It’s the mother of a daughter, who has had an awful accident and has stayed in the hospital 52 days and counting, who comes down every day with a smile on her face. It’s those people that you’re like, “I can smile now. I’m gonna be OK, but let’s be strong for others.”

Q: Why is this job important to you?

A: I believe in affecting people. I love it. I love helping people. I love changing people. I love making an impact: that is my ministry.

By Ashleigh Atasoy

Jackson Dubinski (17): Team Player with Honors

Now, after three seasons of growing into his jersey, junior Jackson Dubinski has gained a leadership position on the basketball team and an All-District award.

“To have success my first year and to be at least dressing out on varsity and being a part of that team was really cool because it kind of inspired me to come back the next couple years and try to do what they did,” Dubinski said. The award “meant a lot because it was one of my goals looking forward from the beginning of the year. … That kind of left a good note at the end of the season, knowing that I won All-District.”

The basking didn’t last long though. Golf tryouts began the following Monday. On the heels of postseason accomplishment in basketball, Dubinski looks for another All-District recognition in varsity golf for the second time. More than acclaim, the basketball award only reminded Dubinski of improvements to be made. The pride of his recognition has been pushed to the side as he prepares for a fresh season and focuses on what he can do to better his team as a whole in the coming year.

“I’m not really big into individual stuff,” Dubinski said, “because obviously our goal is to win a state championship, which didn’t happen this year.”

Though these losses were devastating, Dubinski is relieved that his two varsity sports didn’t overlap this year. In the past, especially when games for district and state titles start, the scheduling of two varsity sports becomes overwhelming and hectic, he said. Although the work and dedication required of a double sport letterman can be strenuous, Dubinski finds too much joy in each sport to ever consider letting one go. The contrast from one another is exciting rather than inconvenient.

“I just think you love two sports. Instead of devoting your time to one thing that you love, you love two things,” Dubinski said. “You just want to play both of them.”

With the golf season now in full swing, Dubinski makes team goals his personal ones, using his past decorations in each sport to fuel his energy to succeed on a team.

“I just want to win a state championship,” Dubinski said. “I know that’s kind of an outcome goal and you don’t really have control over it, but a goal that I have control over would just be to continue what I’m doing, showing up and trying to get better each and every day and not really looking forward to anything but just focusing on the here and now.”

By Kaitlyn Marsh

Jude El-Buri (18): Altruist

There is almost confusion in her answer. “Whenever people ask me, I don’t know what to say because I’m so used to saying four.”

Two years ago, March 6, at age 26, Rehab El Buri passed away after a long battle with stage four melanoma. Despite this loss, her youngest sister senior Jude El Buri’s memories are still very much alive.

“In the last few years of my sister’s life, she became really proactive,” Jude said. People “remembered going to the mosque and seeing her with like tubes hanging everywhere on her body. It was below zero out, and she was holding a bake sale for one of her friends. Even though she was really sick, she kept going, and it was a really big priority for her to leave something behind before she would go.”

Only a few days before her passing, Rehab’s husband came to the El Buris’ with a request – not only to remember his wife and to continue her legacy, but to also build upon it and help others learn.

“So we were in the hospital, and her husband came up with the idea. And he said that maybe we could start a small foundation and continue all the projects that she started, and we all agreed on it. And after she passed away, we got tons of [support] through Facebook and text messages,” Jude said. “They were telling me that they had heard my sister’s story and were so inspired, and we were not expecting such a huge response after it happened, so we [said] we should take this opportunity to expand the foundation.”

The Rehab El Buri Foundation, named after its inspiration, is defined by four categories. To respect what Rehab built in New Jersey where she formerly lived, the foundation has sponsored The Give Network, to provide for families or individuals who need services, the foundation has worked to provide money to support small community projects.

The foundation also funds melanoma research and hopes to publish a blog written by Rehab and her experience to raise awareness for the disease, as well as the annual 5K Race to Action held in Columbia. The El Buris also gift journalism scholarships through the University of Missouri-Columbia because Rehab was in journalism before her diagnosis.

“We have so many different purposes,” Jude said. “I feel like it’s still trying to get established. I think when we get the ball rolling, we will start having more community projects and hopefully I would like to see in the future a lot more people aware of the foundation and a lot more participation in foundation events.”

Since helping establish the charity, Jude assumed the role of “secretary” because the majority of the work Rehab’s husband does as president deals with legal issues. However, Jude hopes to eventually take charge of REB. She wants to make the foundation more widely known, she said.