Some women, especially feminists, have such a sharp sense of political correctness that they could easily point out film characters’ lack of believable traits. In a male-dominated entertainment industry, female viewers want realistic characters that represent their gender, role models that young girls can look up to and be inspired to move beyond any gender limitations.

When somebody is discussing a movie and its tropes, a feminist film buff might mention the Bechdel test, or as I like to call it, feminist media checklist. Named after a graphic novelist Alison Bechdel, it asks about the realistic portrayal of women in media, specifically female characters who don’t talk about men. It first appeared in one of her earlier works, “Dykes to Watch Out For.”

One of Bechdel’s comic strips features two lesbian characters going out to see movie in the theater that plays nothing but “guys” movies. As the first character explains, she will only watch movies that follow three criteria:

1) It includes at least two women

2) who have at least one conversation

3) about something other than men.

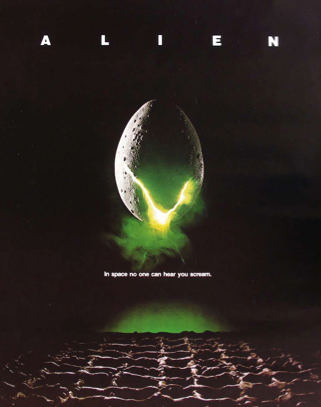

The last movie she watched? “Alien.”

The feminist community of the internet helped to popularize the test; they often used this criteria to judge films, T.V. shows, literature and other media to determine how female-friendly it is. In 2013, the Swedish Film Institute gave Swedish cinemas and television channels the go ahead to incorporate the Bechdel test into their ratings.

This rubric helps some writers to create a story and characters that don’t offend any genders. Unfortunately, following the Bechdel test in writing doesn’t mean you can write strong female characters. Even movies with authentic female characters with tough personalities failed to pass the test.

Bob Chipman of “The Escapist,” while agreeing with every point about female misrepresentation, was critical that people were making too much of one movie passing or failing. He pointed out that movies like “Terminator 2: The Judgement Day” and the recent “Pacific Rim” both have strong female characters, yet they never passed the criteria. However, some B-movies with sexualized women and even “Twilight” movies get a pass.

I agree with the purpose of the Bechdel test, but I also agree with Chipman. However, my personal beef with this test is not passing or failing, but the broad and vague description of Rule Number 3: talking about something other than men.

I could come up with a lot of scenarios where two female characters talking about male character that has nothing to do with their so-called romantic life. For example, a female detective and her female assistant come to the crime scene and discuss the profile of the male sociopathic culprit. Does this count as not passing rule number three of the Bechdel test?

Or how about a mother talking about a concern regarding her teenage son with his female teacher. Does this scene seem sexist to you because it doesn’t live up to number three?

If you, the feminist theorist, look at these imaginary scenes in different angles, you could see that these are mostly about women coming to recognition of their personal conflict. These female characters I have created aren’t used as parts of pieces of a Victorian romantic plot, but rather as regular people dealing with their own conflicts.

And another thing, if I can abuse this loophole even more further, what if the women only talk about cleaning, staying at kitchen, sandwich recipes, manicures, dresses etc.? Does that count as “representing” realistic and strong female characters?

Following the rules of the Bechdel test doesn’t make the story and the cast more realistic and less bigoted, but rather, it has moved far away from promoting feminist ideology.

The movie “Pacific Rim” features a woman named Maki Mori who never has a male love interest or a conversation with another female character, and yet she has a fresh characterization, something a feminist would be proud to see. Sadly, this movie didn’t pass the test because Mori never talked with another female character in this movie.

Because of this, Chipman made his own alternative test called the Maki Mori test, one that judges films whether they have:

1) at least one major female character,

2) who has fully-developed story arc,

3) that doesn’t revolve around a male character.

I like this alternative, because it makes it very clear how to have a strong female character in a story without having more female characters.

As a matter of fact, there are several political dogma rubrics that actually do better jobs of offering a realistic portrayal of minorities in the media. GLAAD, a LGBT right organization, created The Russo test, named after co-founder and film historian Vito Russo, that presents itself more verbosely than Bechdel’s. GLAAD suggests that movies should be evaluated in three grounds:

1) The film contains a character that is identifiably lesbian, gay, bisexual and/or transgender.

2) That character must not be solely or predominantly defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity. i.e. they are made up of the same sort of unique character traits commonly used to differentiate straight characters from one another.

3) The LGBT character must be tied into the plot in such a way that their removal would have a significant effect. Meaning they are not there to simply provide colorful commentary, paint urban authenticity, or (perhaps most commonly) set up a punchline. The character should matter.

Not every story in the media should meet these criteria, but if you want to create fictional gay characters, you need to consider these rules. Despite being longer than Bechdel, the rules are more solid and less paradoxical.

The existence of the Bechdel test may be well intended, but it does nothing to promote feminism and all it does encouraging girls to nitpick about lack of female characters. Furthermore, the test doesn’t give anyone a keen insight into female struggles.

By Jay Whang

What are your opinions on the Bechdel test?

Caylea Erickson • Feb 24, 2014 at 11:17 am

I understand what the test is trying to do but it doesn’t help women at all, like Nicole said it’s more of a guideline but it’s not detailed enough to actually do anything

Nicole Schroeder • Feb 23, 2014 at 10:48 pm

I think that the Bechdel test is, at least in some instances, more a set of guidelines rather than strict rules. It could be used more to draw attention to the issue of weak female characters in many movies these days, and I believe that that is a greater reason as to why the test is so broad. It can be used as a guide, but it is more likely an attention piece for movie-goers.