The Great Wave off Kanagawa, better known as The Great Wave, is one of pop culture’s most iconic images. The famous woodblock print was created around 1831 as an addition to a series of woodblock prints, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Sanju-roku Kei), made by the artist once known as Katsushika Hokusai.

Despite having made monumental advancements in Japanese art during and after his time, Hokusai had never been fully satisfied with his work, not even as he faced death. However, his life story is still a fascinating story that has ended up changing Japanese society.

Katsushika Hokusai’s life is best divided up into time periods associated by his various names, which just so happen to correspond to his various art style changes. During his lifetime, Hokusai, originally named Tokitarō, underwent at least 30 name changes during his lifetime, with his most famous name being that of Katsushika Hokusai, associated with his time of rising artistic fame in Japan in 1798.

Although this was not the time period in which he created his world-renowned The Great Wave off Kanagawa, Hokusai published two landscape collections, Famous Sights of the Eastern Capital and Eight Views of Edo, as well as developed a following of his own pupils, increased notoriety and a development of his own distinctive art style.

Within the next decade his fame grew not only through his art but also his knack for self-promotion. Stories of Hokusai speak of him “painting through performance” rather than through traditional and more conservative tactics. One retelling of a story places Hokusai at a Tokyo festival in 1804, in which Hokusai created a 600 foot portrait of the Buddhist priest Daruma through using a long brush with bucketfuls of ink.

Another story states that he was once invited to compete in a live-painting session held in the court of the Shogun Ienari. Rather than painting through traditional brush and ink, Hokusai’s technique could be described as more “abstract.” The Shogun himself watched as Hokusai’s act began with a single blue curve on a sheet of paper which was followed by him chasing a chicken, whose feet had been dipped in red paint, across the courtyard and back. He claimed his work was a landscape showing the Tatsuta River scattered with floating red maple leaves and won the competition.

It was after the age of “Hokusai” that he began creating the paintings renowned today that secured his later fame overseas (Japan was isolated from the outside world at the time, so overseas fame came only after Hokusai’s death). In 1820, “Hokusai” became “Iitsu” and reached the peak of his career. Hokusai’s love for Edo, Japan (now modern-day Tokyo), was featured through his various woodblock landscapes including his most famous works, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces and Unusual Views of Celebrated Bridges in Provinces. The Great Wave was also developed during this time period. The famous woodblock print was created around 1831 as an addition to a series of woodblock prints, Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku Sanju-roku Kei), and features a large rogue wave with Mt. Fuji in the background.

The Great Wave is one of pop culture’s most iconic images and has been recreated on countless notebooks, t-shirts, and other memorabilia. The art depicts a large wave that encompasses about ⅔ of the print, as well as several boats caught within the storm. Mt. Fuji can be seen by viewers cowering under the cresting wave, hinting at Hokusai’s everlasting love for the grand mountain but also showing Hokusai’s clever play with perspective. Fisherman are also seen braving the wave, and seem to be suspended in a moment before their doom.

This theory has also lead to many believing the art depicts not only a wave, but also a monstrous tsunami terrorizing Japan, although both myths have likely been proven untrue. Hokusai himself had never experienced many tsunamis, and the boats pictured were slim, swift, and designed to transport fresh fish through various conditions, including turbulence.

His unconventional tactics were not the only aspect of Hokusai’s art that distinguished him from other artists. Hokusai was well-versed as a ukiyo-e printmaker and had been studying the style since he was 18 under the name “Shunrō”. As Shunrō, Hokusai studied at the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō, an artist of ukiyo-e. Ukiyo-e focused on a style of woodblock prints and painting, a skill quickly mastered by Hokusai, and traditionally featured courtesans (a prostitute with wealthy, upper class clientele) and Kabuki actors (actors of classical Japanese dance-drama). The artist later published his first prints, a series of works of Kabuki actors, in 1779, and continued practicing traditional ukiyo-e art until he got bored of it.

Upon the death of Shunshō in 1793, Hokusai ventured into other styles of art, namely European styles he was exposed to through French and Dutch copper engravings he had obtained, and also began studying under other schools, even his studio’s rivals. This “betrayal” may have gotten Hokusai into trouble, as he was soon banned from the studio by Shunshō’s chief disciple Shunkō.

On the other hand, rather than dwelling in self-pity, Hokusai was inspired. Afterwards, Hokusai changed the subjects of his works and that of the traditional ukiyo-e. Instead, his works featured landscapes and the daily lives of Japanese people, a breakthrough change in both ukiyo-e and Hokusai’s career, which would lead to the era of “Hokusai” and other important advancements. When reflecting upon his developments, Hokusai was thankful of his excommunication from the school, saying: “What really motivated the development of my artistic style was the embarrassment I suffered at Shunkō’s hands.”

Hokusai, although a master at ukiyo-e, had not limited himself to only that style of art. In 1811, at the age of 51, Hokusai changed his name to Taito became well-versed in creating various “etehon”, or art manuals, as well as his famed Hokusai Manga. His works influenced the art of modern day Japanese storytelling, specifically a style of graphic novels known as “manga”. His versions featured sketches of flora, fauna, landscapes, and the supernatural and were block printed in three colors, black, gray and a pale beige. These three colors and styles in particular are seen in Japanese manga today.

In his later years when his fame declined, he wrote in the postscript of One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji: “From around the age of six … from fifty on [I] began producing works that won some reputation, but nothing I did before the age of seventy was worthy of attention … If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am eighty-six, so that by ninety I will have penetrated to their essential nature. At one hundred, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at one hundred … or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive.”

In this reflection of his life, Hokusai talks about as he grew older, he continued his pursuit of becoming a “true artist” and his progressive growth from when he started drawing, at age six, to his current state of life. His constant search for artistic growth was the motivation that kept him going through as he continued painting through the age of 87, painting such masterpieces as Ducks in a Stream. Even in his deathbed Hokusai stated, “If only Heaven will give me just another ten years… Just another five more years, then I could become a real painter.”

LATEST NEWS

- Stress, anxiety skyrocket as students prepare for upcoming AP tests

- RBHS holds successful night of percussion

- Not even water?

- Solar eclipse to pass through Missouri, April 8

- How CPS is organized: a guide

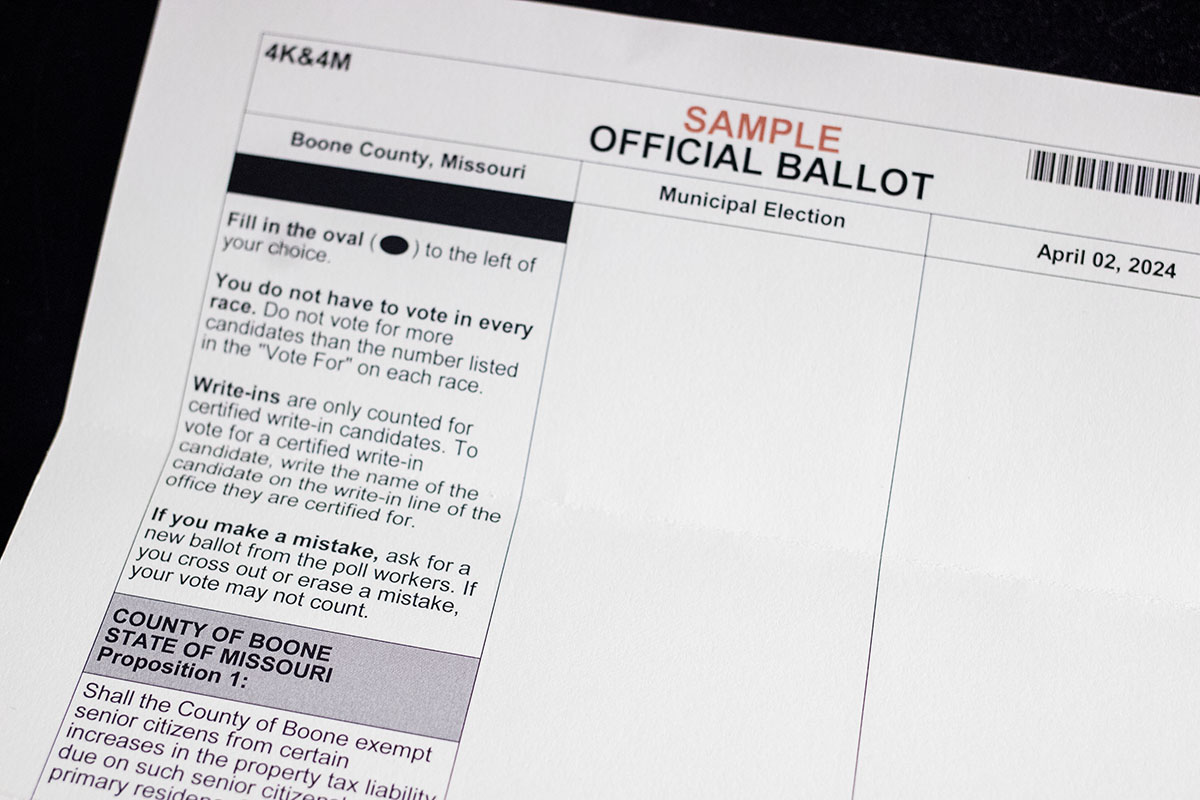

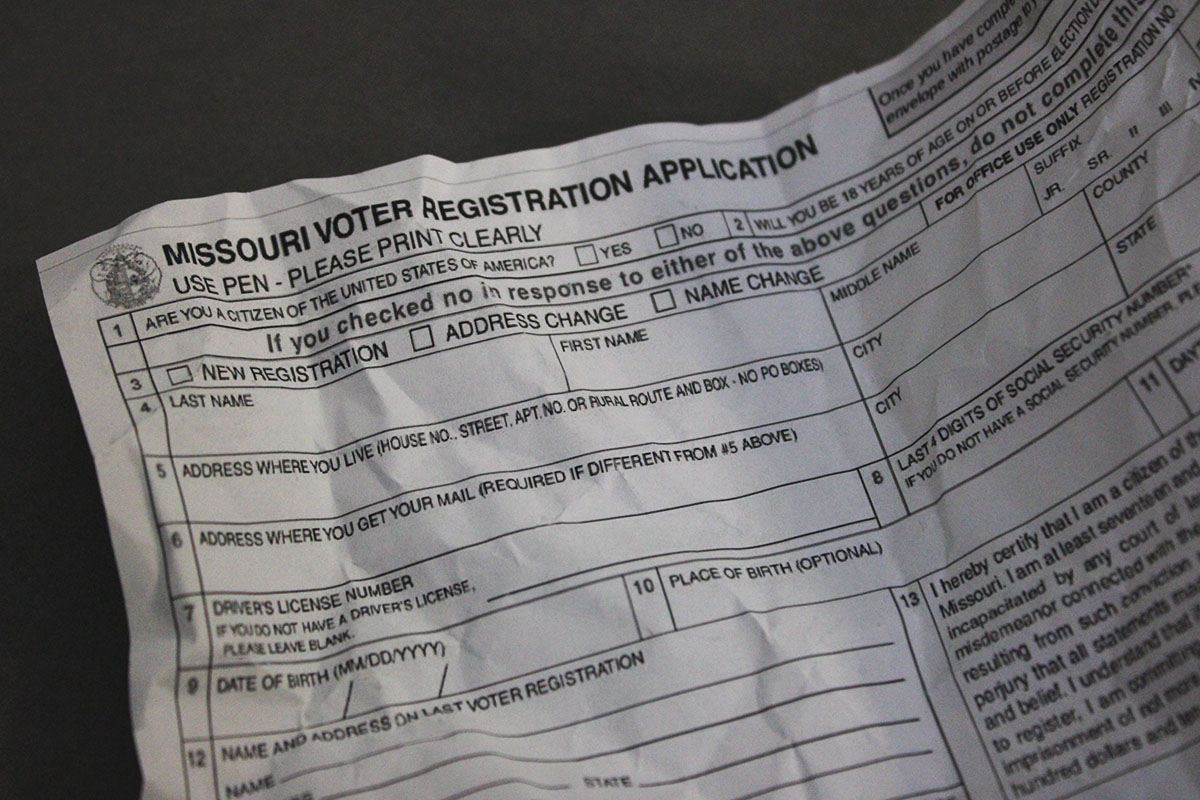

- City of Columbia to hold school board election April 2

- Youth Election Participants to assist in upcoming municipal election

- City of Columbia hosts first Community Engagement Session for McKinney Building, hopes to gain public insight on the structure’s future

- RBHS Track Team Opener at Battle Gallery

- March Mathness Photo Gallery

An analysis of Katsushika Hokusai

November 9, 2016

Leave a Comment

More to Discover

@2021 - www.bearingnews.org