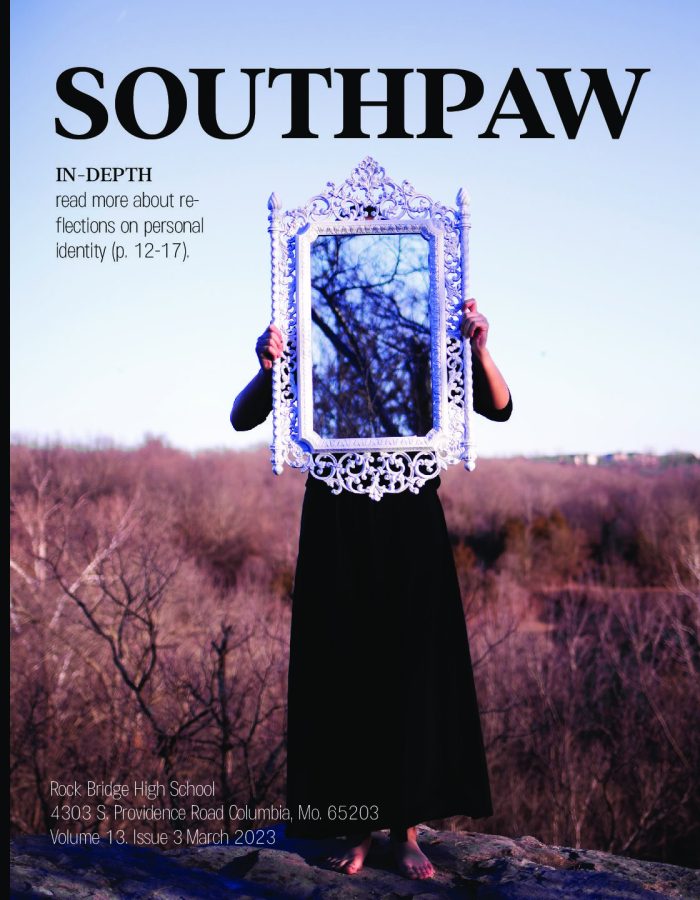

Southpaw: What Next?

[tabs active=”9″] [tab title=”What next?”] [heading size=”20″]Beyond high school[/heading] Dreams for the future fill our minds from the time we enter preschool. Fantasies of potential colleges, professions and lives grip our thoughts throughout the years of primary and secondary school as we grow hope for prosperity, happiness and success in adulthood.

We set our goals, envision our dreams and focus on our ambitions, hoping they will bring us joy. Even through our common goal, the one universal, education, can be vastly different for each of us. School can help us cultivate our dreams or it can suppress our ambitions. School is not our only source of education, however. Faith is a learning experience in itself, and as we grow we must balance the religious ideology of our families with our personal goals for our future.

After years spent exploring our abilities in high school classes, we find our strengths and weaknesses and determine what we are truly passionate about before we leave the safety of adolescence and enter the world in pursuit of success, a long life and a prosperous future. Our educational backgrounds, social classes and religious ideologies are vastly different, but we can overcome these rifts if we look at what connects us.

By Emily Franke and Sophie Whyte

[/tab] [tab title=”Success”] [heading size=”15″]When education fails: teachers, students question the role of creativity in modern classrooms[/heading]

“Luckily, I didn’t have to give grades in my program, so we weren’t focused on grades, we were focused on learning,” Toalson said. “I think grades can work as an incentive but they can also take away from the process of learning.”

Dr. Sara Truebridge, education consultant to the documentary Race to Nowhere and author of Resilience Begins with Beliefs: Building on Student Strengths for Success in School said the letter grading system used by American public schools is an ineffective method of measuring students’ abilities. The grading scale does not offer a full representation of a student’s academic standing, she said, as components are often unclear.

“In most cases grades, at best, only reflect performance and does not necessarily reflect skills and the processes that go into learning and progress such as effort or higher level thinking,” Truebridge said. “Furthermore, as a tool for feedback, grades have limited value because there is no depth to understanding exactly what went into that grade. That also speaks to the lack of consistency in grading practices.”

The current system of grading is not only a poor representation of students’ effort and capability, but an ineffective tool in promoting students’ learning, senior Carly Rohrer said.

Rather than encouraging students to interact with and understand the material and content, Rohrer said, grades lead students to cram information before exams and subsequently forget this potentially useful knowledge.

“All you’re working towards is to get an A or to pass a class, you’re not working towards actually getting interested and getting involved in what you’re learning and putting it to use,” Rohrer said. “I feel like all that we do is try to remember things and then spit it out on a test and then after that we don’t care about it; we don’t remember it anymore.”

This detachment from genuine learning may be causing a dramatic drop in the divergent thinking skills of teens and adults. In the late 1960s, George Land and Beth Jarman conducted a study measuring the divergent thinking skills of kindergarten students between the ages of three and five.

Divergent thinking, as defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, is “creative thinking that may follow many lines of thought and tends to generate new and original solutions to problems.” These skills allow people to simultaneously consider various alternative solutions and encourage a mindset that fosters originality.

The study, as described in their 1992 book Breakpoint and Beyond: Mastering the Future – Today, found that 98 percent of tested kindergarteners scored in the top tier of divergent thinking skills, a category labeled “genius.” Five years later, the same students took the test once again, but only 32 percent scored in the top tier. Then, after another five years, only 10 percent scored in the top tier. In 1992, only 2 percent of 200,000 adults scored in the top tier of divergent thinking. The public education system, in which young, malleable-minded children spend so much of their time, could be the reason behind this extreme decrease in the ability to think creatively, Toalson said.

“I think [the school system] definitely does not promote creativity,” Toalson said. “Today, kids are pretty much taught at home and at school ‘don’t get into trouble and don’t do anything outside the box.’”

Toalson said the lack of education-inspired ingenuity is cause for concern. If the future adults of our country aren’t taught to think outside of the box, they will be less apt to deal with real life issues in the future.

“I don’t think students are encouraged today to be creative, and I think that’s really bad,” Toalson said. “If your best thinkers aren’t thinking creatively, who is going to be solving world problems?”

Toalson is not alone in her opinion that the school system is missing an essential component of originality. In 2012, Adobe performed the State of Create global benchmark study, surveying groups of individuals from the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Japan. The study reported that 70 percent of surveyed individuals from the United States feel that creativity is taken for granted within our modern culture, while 62 percent agreed with the statement that our educational system stifles our creativity. Rohrer agreed the public school system seems to take away from the creative thought process by limiting students’ educational options.

“We promote creativity to an extent, but it seems like we talk the talk more than we walk the walk,” Rohrer said. “We promote [creativity] and everything but then our class selections are so limited and only appointed to certain subjects. You have to have all these core classes and all these requirements, and if we really wanted to get people ready for careers, we should have them doing things they want to go into.”

Society’s cookie-cutter definition of success may be confusing students’ idea of what constitutes achievement, Truebridge said. The competitive frame of mind encouraged by modern schools does not allow for purpose-driven learning, and Truebridge said this detracts from a cooperative outlook on the world community.

“I believe that we have really created a system where we have become a bit too myopic and are equating success with such things as getting good grades, getting into name colleges, getting a job that is lucrative, and being ‘the best’ in a world that many continue to frame as ‘competitive’ instead of ‘cooperative,’” Truebridge said. “Before having a discussion on whether the school system is effective in preparing students to be successful in today’s world, I would rather have a discussion on how we define success and how we can support the reframing of our lens to view the world as cooperative instead of competitive.”

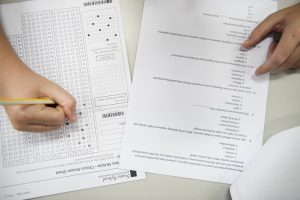

Students’ performance on standardized tests suggest our country’s youth may hold a poor academic standing, especially compared to kids in other countries. The Annie E. Casey Foundation reported that one-third of all students scored “below basic” on the 2009 National Assessment of Educational Progress Reading Test. On the same assessment, 32 percent of eighth graders and 38 percent of twelfth graders scored at or above proficient for their respective grade level. Math and science scores are even more sobering.

In 2012, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development performed an assessment ranking the mathematical and scientific abilities of teens from 30 different countries. Fifteen-year-olds in the United States placed 25th in math performance and 21st in science performance, suggesting that perhaps our country’s current system of teaching is not giving American youth an advantage as future members of the global economy.

Aside from placing a greater emphasis on creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, Toalson said the education system can be improved by cutting down school and class sizes dramatically, in order to ensure individualized attention to each student. She said classes have grown too large for their teachers to cater to the educational needs of each individual, which is vital to these students’ academic success.

“If we have schools with 2,000 kids, I think that’s the real problem,” Toalson said. “Fifteen years ago in Rock Bridge they said no teacher had more than 80 students. I think now most teachers probably have close to 200 students, so how can they give you the individual attention that [students] need?”

School should strive to create an environment that nurtures students not only academically, but also on a personal level, Truebridge said. Ideally, she said students should feel safe, respected and encouraged in their educational surroundings.

“The other area that I think needs more attention, and research confirms this, is ensuring that education focus on addressing the needs of the whole child–cognitive, physical, social, emotional and spiritual,” Truebridge said. “One way to accomplish this is to focus on school climate and what some refer to as ‘the hidden curriculum.’ This includes maintaining a strengths-based perspective; recognizing that learning happens by addressing the heart as much as the head; and believing that all students have the capacity for resilience and are able to learn and thrive when provided with the appropriate protective factors: caring relationships; high expectations; and opportunities to participate and contribute.”

Rohrer asserted the importance of individualized education when it comes to students’ well-being. Like Toalson, she suggested decreasing class size and increasing the teacher-to-student ratios. Even though educational reform would demand lots of time, money and hard work, Rohrer said it is the best option for students.

“There’s just not enough time for teachers to talk to each individual student and take care of their individual needs,” Rohrer said. “We need more teachers. We need smaller classes. We need more classrooms, but that’s just a lot of changes to make. In the long run, though, I think that’s what we have to do.”

Truebridge said caring about the varying needs of different students is vital when it comes to fostering an effective learning environment. More than anything, she said, caring passionately about each student will make the biggest difference in whether or not American youth thrive in today’s schools.

“Something that I say in my book, Resilience Begins With Beliefs: Building on Student Strengths for Success in School is that when asked, ‘What needs to be done, if anything, to improve the public education system in our country?’” Truebridge said. “I answer simply with the following: Love and hug the students.”

By Anna Wright

[/tab] [tab title=”Expectations”] [heading size=”20″]Born for success or fighting the odds?[/heading] When leaves begin to blush and shiver at fall’s chill, high school seniors across the nation retrieve their worse-for-the-wear backpacks from the depths of their closets, emptying them of old gum wrappers and crumpled tests shoved, unwanted and defiled with red pen, to the bottoms of bags.

They meticulously plan their first day outfit, eat a breakfast fit for champions and head to their last first day of high school. For many, the routine is the same; the school is the same. What they’re about to walk back into is the same. Seniors expect that their school experiences are the same as most other seniors’ experiences, but for many this isn’t the case. RBHS guidance counselor Samuel Martin believes that students physically go to the same school but, at the same time, don’t go to the same school at all.

“Schools for the most part in the U.S. are designed from a Eurocentric, middle class, middle America perspective,” Martin said, “and there are a fair amount of people with poverty in their backgrounds that don’t come from that perspective. You go to a school and in one sense, everybody there’s speaking the same language, but in another, they’re not.”

Martin believes this disconnect between perspectives and cultural backgrounds contributes to the achievement gap, or the disparity in academic performance between groups of students, troublingly often perceived between the academic performance of students from low-income and high-income families. An October 2013 Board of Education Student Performance Report shows, for example, that students on Free and Reduced Lunch consistently score lower on standardized tests, have a significantly lower graduation rate, have higher out-of -school suspension rates and take far fewer AP classes.

Jake Giessman, co-director of the Center for Gifted Education, said the achievement gap has been a persistent problem in the nation, one that’s still at the forefront of the education community’s focus. He put forth a different potential cause for the disparity.

“Some people think that if you’re from an impoverished household, you have less of an opportunity to learn early on,” Giessman said, “like your parents aren’t sending you to preschool, you’re not given any learning toys, the family doesn’t read a lot for fun, talk about politics, use big vocabulary at the dinner table, maybe isn’t really sure about the value of education because it was a bad experience for them … so people hypothesize there might be a cumulative effect.”

“I think there is a correlation, but I also don’t think that proves causality. I don’t think the fact that one is without funds means that one shouldn’t be motivated,” Matthews said. “I come from a place where we just don’t have. And that makes me more motivated so that one day my kids won’t have to not have. People use their situation as a crutch. ‘Because this is happening, I can’t do this.’ You can do whatever you want to. You need to make the decision on a personal level to not focus on what’s going on now, but to focus on what you hope will go on in the future.”

Matthews didn’t have much technology growing up. She often couldn’t afford to go on school trips because of funds or transportation. Martin believes this disparity in available opportunities is a part of the problem.

“Part of the achievement gap is an opportunity gap,” Martin said. “If I grew up in a house where my dad speaks two languages, travel all the time, I’ve been exposed to opportunities that my friend growing up in a single parent home won’t have access to. Just through my opportunities, I’m benefitting.”

Along with family background, Matthews believes stigma plays a significant role in widening the achievement gap. She sees negative connotations attached to being lower-income and still wanting to try hard academically.

“I’ve been told so many times, ‘I don’t know why you’re in an AP class. You’re on food stamps,’” Matthews said. “Well, because I don’t want to always be on food stamps, I want to do better with my life.”

Though Martin believes the stereotype exists, he also said it is sometimes more imagined than real, especially at a school like RBHS where authenticity is valued. Personally coming from a high school where students were respected for intellect and went to Ivy League schools regardless of background, Martin doesn’t buy into the idea of an anti-intellectual ideology amongst lower-income students.

With the significance of family background, early educational opportunities and early-formed mindsets largely agreed upon, the weight of the first several years of a child’s schooling and upbringing swells. Martin says at the high school level, though the mindsets formed during childhood about personal ability and the value of education can be hard to break into, it’s doable and an effort that schools must make.

“I think school always has to tell kids that they are capable, that hard work pays off, that where you end up is more important than where you start, teach academic resiliency,” Martin said. “As much as I try, I’m just not going to be a superstar athlete — you can’t really affect that. My intelligence? I can affect that. I can control that. I can impact that. On the other hand, I have to make sure that I’m doing what I can to better myself; I have to take on that initiative. In society, there are wrongs and ills and inequities, but at the end of the day, it’s on you to decide what you do with it.”

Matthews, who has lived in this “inequitable” system for the last 12 years, believes bridging the opportunity gap will be what engenders the change in the achievement gap.

“It honestly starts with recognizing that yes, not everyone’s going to be afforded the same opportunities, but everybody should be,” Matthews said. “And of course it’s not plausible to afford it to everybody, but just recognizing that everyone should be, making everyone equal, that’s what’s gonna break it, that’s what’s gonna make it about not about how much money your parents make, but about what you can achieve.”

By Urmila Kutikkad

[/tab] [tab title=”Change”] [heading size=”20″]Branching out: discovery through faith[/heading]

Coming from a Catholic family, Johnson made the bold step of leaving his parents’ church and following his own heart. He realized he did not agree with some aspects of Catholicism and started leaning toward Protestantism.

My parents “were really upset. My mom was crying, and my dad was just frustrated because, as a Catholic … when they baptize babies, during the baptism they say ‘OK, Mom and Dad, do you promise to rear this baby up as a Catholic?’ and they say, ‘Yes, yes we do,’” Johnson said. “So they kind of feel like they’ve failed in this duty.”

Johnson knows the process of accepting his conversion will be long and difficult for his entire family. However, he wants to convert because he feels it is necessary to identify himself with what he truly believes. Since they don’t understand the logic behind his life-changing decision, Johnson believes as long as his parents do not try to understand the way he interprets religion, they will not be able to fully accept the change.

“There’s no real way for them to feel better about it unless they convert to Protestantism and be like ‘Oh, it was never really necessarily right of me to make him Catholic because Catholicism is wrong.’ But that’s really the only way to make it OK,” Johnson said. “Besides that, I think they’ll be frustrated with me. When I told my dad, I said, ‘Dad, what’s really the worst that could happen if I go through with this Protestantism thing?’ and that’s not saying that I might not go back to the Church if I somehow agree with it again. And he said, ‘Seth, I’d probably lose a little bit of respect for you as a reasoning person,’ because he thinks he’s right.”

Johnson’s first exposure to the idea of officially converting to Protestantism occurred a few months ago when he started weighing options for college. At that moment he realized he needed to make a solid decision soon since he was exploring the idea of attending a Protestant college.

“College was coming up, and my idea was going to a Protestant school, not a Catholic school. Because for me, I like surrounding myself with people who agree with me, especially [in] college because you’re setting yourself up for the rest of your life,” Johnson said. “So I thought ‘Man, I better figure this out now, before I get going.’”

Since his parents do not agree with his change in faith, Johnson let go of the idea to attend a Protestant college because his parents will not finance his education there.

Johnson is still in the process of converting and becoming a Protestant, and he is still weighing both Catholicism and Protestantism and attending events for both faiths. But he admits he favors Protestantism, and will probably go through with his conversion in the near future; however, Johnson is not alone.

According to Pew Research Center, most people who change religions do so before the age of 24. Overall, 44 percent of the adult population in the United States chooses to leave their childhood faith, according to the 2007 survey. Out of the 44 percent, though, only five percent are Protestants who were raised in a Catholic household.

Johnson now believes in Protestantism because he agrees with its theological interpretation. Although Johnson’s parents disagree with him, he believes the differences are minor and focuses on commonalities between the two sects of Christianity.

Along with his parents, Johnson’s 14-year-old sister also debates his new faith. She often questions Johnson and his decision, and the two get into arguments because she believes in the Catholic faith.

My sister “is siding with my parents. She can be kind of snarky about it too, cause she’s 14. She’ll question me on things and I’ll explain myself to her, and I can usually out-argue her,” Johnson said. “I’m not trying to convert her, ‘cause that would be a really big deal, but I’d say ‘Have you ever even considered this?’ and she’ll go ‘I will never not be Catholic.’”

It is not uncommon for such rifts to occur among relatives. Parents tend to shut out children who stray from the religion or belief system the rest of the family follows, said Darren Sherkat, professor of sociology and department chair of sociology at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Although Johnson’s family did not react in this manner, Sherkat points out some families will become divided and children will not receive as much attention from their parents.

“Children who deviate from their parents’ religion are often shunned and do not benefit from parental resources,” Sherkat said. “This is especially true for women who deviate from the faith of their parents. Often, children simply fake adherence and participate grudgingly so that they can avoid sanctions from their parents and other family members.”

Sherkat also thinks the reason religion is so important within families is the social aspect; when relatives have the same beliefs, it is easier for them to have a strong bond and a sense of understanding since religion is often an integral part of many families, Sherkat also said he believes it has the ability to make or break family bonds.

“Religion is important partly because of beliefs and values that parents want to be instilled in children through religious indoctrination, but also equally for social reasons. Religious organizations are important settings for intergenerational interactions and social bonds and status are adjudicated in such institutions,” Sherkat said. “There is no necessary relationship between religion and family values, and many religious values wind up dividing and destroying family relations.”

Even though Johnson’s family doesn’t accept his new faith, growing up in a household with conflicting religions isn’t always a problem in itself. RBHS science teacher Cathy Dweik grew up in such a household. Dweik’s father was Presbyterian and her mother was Catholic, both different sects of Christianity. Because neither parent actively practiced their religion at home, Dweik didn’t feel a struggle to differentiate between the two. Instead, she believes the circumstances of her childhood helped her become more accepting of other religions.

“I’ve seen people pitted against each other in the media based on religion where each believe their’s is the best religion and the other faiths are underneath; they’re not as good’ for whatever reason,” Dweik said. “And I never felt that … on my dad’s side or my mom’s side. I didn’t ever experience [the thought] that this one’s better than the other one. And because I had a chance to go to different churches with my grandparents, cousins and friends, I saw the similarities instead of focusing on the differences.”

Sherkat said the hostility Dweik saw inflicted by opposing religions is indeed real, and a big problem. He said that there are people in almost every religion who do not view the rest of the world’s religions with an open-mind, like Dweik and her family.

“The difference among groups is more about religious fundamentalism than it is about the specific structure of beliefs about the supernatural,” Sherkat said. “Religious fundamentalists from all religious traditions … view other groups in a very negative light, and it is a small step from viewing people as spiritually inferior to seeing them as a social problem needing eradication.”

Sherkat also points out the different ways followers of a religion interpret the intricate details contribute to the conflict religion can cause. In Johnson’s case, the conflict he has with his parents is based on different interpretations of the Bible and other religious traditions.

“Research consistently shows that religion increases prejudice and discrimination towards people who do not subscribe to the beliefs of the dominant tradition,” Sherkat said. “In all faiths, devotees can point to passages in sacred texts that either call for tolerance or genocide for non-believers, and there are movements in all religions that promote peace and prosocial behavior, and movements that promote prejudice, discrimination, and violence.”

When Dweik was growing up, she did feel some religious pressure from her mother’s side of the family.

“My grandparents … were encouraging me to become Catholic by taking me to catechumens classes, but I attended Baptist, Christian and Presbyterian churches with my cousins and friends as well. The benefit for me was that I was able to attend services of different religions,” Dweik said. “And that may be why I’m more open-minded in that respect, because I saw the similarities in all of them.”

As a child Dweik never felt the need to identify herself with just one religion. When she grew up, though, Dweik met and married a man who followed a different religion than either of her parents. Her husband followed Islam, and after nearly 10 years of exposure to the religion, Dweik decided to convert.

“My husband was thrilled, but I don’t think my children really knew the difference because they were young. I’d been learning and practicing with them for so long, that it was it was more of a formality in the end when I officially converted,” Dweik said. “Some people go through a radical change in a very short period of time, and for me it just wasn’t that, it was gradual.”

When she first got married, Dweik felt no pressure to convert to her husband’s religion, just as her parents didn’t force her to choose a religion while she was growing up. However, she felt she should raise her children in a household with a single religion and is therefore more closely knit, and she worked hard to provide that kind of stability for her three kids.

“When we decided to have children, my husband and I agreed that since he was stronger in practicing his faith than me, we would be unified in that respect and raise our children following his religion,” Dweik said. “That was important for our children and for that reason, they were raised in a Muslim household.”

Dweik didn’t deal with conflict after her conversion because of the open-minded nature of her relatives and friends. Similarly, for Johnson, friends provided much-needed support during the process of his conversion to Protestantism.

“My friends have … supported me on it. I didn’t have a lot of Catholic friends, [but] I had a lot of Protestant friends, so they were of course supportive of this possible life-changing thing,” Johnson said. “I go to a Catholic church and do a little bit with a Protestant youth group now because I think it’s fair to still continue to weigh which faith is better.”

He believes these commonalities outnumber the differences between the two religions, but those differences are still significant enough to create a divide between him and his family. Even though tensions lower than when Johnson first broke the news there is still a rift within the family that cannot be overlooked.

“This is a recent development, so it’s pretty fresh in [my parents’] minds right now. Sometimes they’ll poke fun at me with little things. They’ll just joke around with me, like when I do something silly, they’ll be like ‘Oh, it must be the Protestantism in you,’ or something like that,” Johnson said. “They aren’t meaning it to be actually true, but they’ll tease me about it.

But you know that subtly they want me to come back to the Catholic faith.”

However, he remains optimistic that the conflict that created a rigid wall between his beliefs and those of his parents will eventually subside, and, with time, his family will understand his decision.

“I think it will smooth itself out with time, especially considering … the division we have is a lot less serious than if I wanted to be … a completely different [religion],” Johnson said. “I still think Catholics can go to Heaven [but] Catholics don’t think Protestants can go to Heaven and all that, but I think it will eventually smooth itself out.”

By Afsah Khan

[/tab] [tab title=”Pressure”] [heading size=”20″]Looking for success under parental pressure[/heading] Growing up, kids face various every-day pressures: what to wear, what to eat, when to get homework done. Although these things may seem small, teenagers especially are constantly being pressured in order to fit in with their surroundings.

Aside from these pressures, teens can receive pressure from their parents or other adult figures. For senior Caroline Sundvold, her parents push her to achieve academic excellence particularly at the end of the semester when grades are most important.

Teen ambition isn’t always fully accepted under parents’ dreams. They push their kids as they grow up to thrive later in life and put ideas in their heads by nature and what the kids are exposed to. Parents often push their kids to have beliefs and ambitions similar to theirs, sometimes to the point of brainwashing them.

What parents may stand for or want in life isn’t always the same as the way their kids’ minds work- unfortunately, kids don’t necessarily always have the freedom they should when it comes to the matter.

Career paths are important. Adults say after kids graduate high school and college, a majority of parents expect them to make something of themselves and be successful. Today, some parents tend to mistake their career ambitions for what their kids are actually interested in. At the same time, parents may just want their kids to reach their full potential and be successful in a career they feel would suit their kids as it did for them.

Although some parents may put pressure on their kids when it comes to careers, it isn’t always the case. Parents may simply influence their kids to choose the same career as them because it’s such a big part of their lives.

“My dad being a doctor sort of influences me in wanting to have a career in the medical field,” freshman Lauren Brummett said. “But he mainly influences me to just want to have a good job and be able to provide for myself.”

The amount of children who choose to pursue the same career as their parents has evolved over the years. According to the website Daily Mail, only about seven percent of kids today end up in the same career path as their parents compared to 50 percent in the 1800s. The explanation for this change is kids today are more ambitious and know what they want, as opposed to what their parents may want from them.

Teenagers say they deserve the right to freely choose what they want to do in life in order to be happy. They, therefore, shouldn’t automatically consider what their parents want them to do to be the correct choice. As kids grow up, their idea of the right career path for themselves can sometimes alter.

“When I was little, I used to really want to be a school nurse like my mom. Now, I’m leaning more towards helping animals and stuff like that,” sophomore Reece Adkins said. “My mom has been really open to my decisions, like she doesn’t push me towards any certain career. She just wants me to go my own way, which I appreciate.”

Some kids know exactly what they want to do in life at a young age; some fantasize about being astronauts, firefighters or ballerinas. As people grow up, reality sinks in and they may look for more achievable options. For some, family members before them pursued the same career.

For senior Erin Concannon, pursuing a career as a doctor just “kind of makes sense” because she comes from a family of doctors.

“I’ve grown up in a family based around a lot of medical careers,” Concannon said. “My dad is a plastic surgeon and hand specialist; my oldest sister is a neurological nurse, my other sister is a physical therapist. Both my parents have really encouraged me to go that route too because they know I’m interested in that kind of stuff and that I have the intelligence to be able to pursue it well. They’ve also pushed me to go to the college that both of them went to, St. Louis University, which is where my dad got his education in medical school.”

By Molly Mehle

[/tab] [tab title=”Faith”] [heading size=”20″]Following faith for a future[/heading]

Some may find it in sports, in academia or even in their family, but wherever passion is, there lies a drive to achieve more.

Teachers and counselors repeatedly push high school students to make decisions and figure out the omnipresent threat of their futures. From the day kids walk into their kindergarten classroom, the question quickly ensues, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ It’s so striking and urgent, and they’re only five years old.

By the time they reach high school their passions are bound to encounter changes after changes because of acquired experiences. What may start out as a childhood passion to be a superhero may become something more mature and self-fulfilling, such as a doctor. For some deciding comes easily; they’ve figured out their passion and are ready to chase it with every ounce of their being. For others, this is a slow process that evokes stress and worry about whether or not things will work out the way they were planned out perfectly in their head.

Senior Kristen Buster wants to be a graphic designer and believes her excitement for her career pursuit originated from her childhood fervor for art. From painting a panel that now hangs in her family living room to creating hundreds upon hundreds of handmade greeting cards, she figured out art was an outlet she found enticing. As the years went on, she broadened her perspective and began to explore the idea of graphic design. By senior year she was able to come up with a realistic way to mold her interests into a career that she could be passionate about.

“It was probably in like eighth grade when I started liking the idea of becoming a graphic designer because I was really into art … I feel like I’m kind of naturally artistic and so graphic design felt like a really natural and practical way for me to be able to use my passion for art in a career field,” Buster said. “I really liked the idea of graphic design because it feels like the modern thing, something that will be more popular in the future and by the time I get out of college and lots of job opportunities in that area and it’s just a practical way for me to use my artistic abilities.”

Once the stress of figuring out what she wanted to do career-wise lifted off her shoulders, Buster began to focus on the meticulous aspects of college preparation. Having her prospect narrowed down, though, is something that put her far ahead of many students, guidance counselor Leslie Kersha said.

“Quite frankly as teenagers you guys are trying to figure out who you are and what your place is in the world, and to be able to know that and what you’re passionate about, that’s a lot of pressure to put on yourself, so I think it should be more about kind of exploring careers and figuring out which of those sound interesting to you,” Kersha said. “If you had a room full of adults and you went around and asked them, ‘What did you want to be when you were 15 or 16 years old?’ I’d be surprised if the majority of people knew exactly.”

Fortunately Buster found her niche quickly through the various design classes she took through Columbia Area Career Center. These classes helped her build skills as well as continue to build on that passion that ignited in her early elementary days. Also, because of her Christian faith, she has grown up in the church atmosphere and has managed to find a way to work graphic design into that environment. Her church, Forum Christian Church, used elements of graphic design, such as visually representing concepts within sermons, in hopes to modernize their outreach to this generation. This enticed Buster, and she hopes one day that she will be able to use her skills to work for either churches or charity organizations.

Since she plans on working in a religious-based setting, Buster was intrigued by the opportunity of going to a Christian college. Many religious colleges are focused on ministry careers, however, and it took extensive searching to fit her career goal into Christian schooling options. After several visits, she decided to attend and live at Ozark Christian College while taking graphic design classes at Missouri Southern State University, both in Joplin, Mo.

“I think I finally decided on Ozark … because it seemed like a really awesome school and somewhere I wanted to go. Just to be there for the environment and the community there, but I never felt like I should go there because I didn’t feel like they had my specific program area. They didn’t have anything graphic design. Obviously it’s a ministry school, so they only had ministry classes, like children’s ministry or theology or worship ministry or stuff like that, so I didn’t think that was my place because I didn’t want to have any of those vocations,” Buster said. “Then when I discovered that they’re doing this co-op program with Missouri Southern and that I can go to Ozark and Missouri Southern State University and get a graphic design degree at MSSU and a Christian ministry degree at Ozark, that was really cool.”

She was able to combine her passion for design with her devotion to her religion and career plans. Because Buster will attend Ozark, she believes she will receive a firm foundation in Christian ministry, something she also feels passionate about. Buster said she feels called to evangelize the love of God in her everyday life, and that’s a calling that she will be working to fulfill whatever career path she ends up in.

“If I want to grow up and be a graphic designer in churches and for churches it would be super helpful and look really good to have a Christian ministry degree also because then I can know what I’m talking about and be able to help Christ-minded clients because, you know, they wouldn’t have to explain the whole religion thing to me because I would know it,” Buster said. “I was just really excited to hear that I could do both because, first, I’m a Christian, and so that’s my true passion, you know, living for God and for His glory and then I would say maybe second I’m wanting to be a graphic designer so it just worked out because it was really nice way to combine them both and be able to satisfy both of my aspirations.”

In addition to her vocation, Ozark’s Christian aspect appealed to Buster. She previously visited other universities and was turned off by the partying associated with college life. Because her studies are important to her, it was vital that she live on a campus suited to her personality and educational intent. On top of all this, she will be in an environment where her peers are all focused on their faith just as intensely as she is.

“I think I was more wanting to do Ozark for the community environment, for the strong foundation in Christian ministry, because even if I don’t go into Christian ministry, I can still use that for the rest of my life and I just like the idea of building something that will last for awhile,” Buster said. “You’ll never stop being called to ministry in life.”

Though her transition from high school into the world of adult and college life was not without trials, Bradshaw was relieved that she was set on a career path by the time she walked into her first college class. She, like most students in high school, had periods when she wavered in her career options. Then, come her junior year at RBHS, Anatomy and Physiology convinced her she wanted to dig deeper; she was going to be a doctor, she was certain of it. However, she felt completely shaken when she sensed a calling towards a completely different, radical and potentially dangerous career path.

“Senior year I’d been having those feelings, like God telling me, ‘You’re going to do missions, you’re going to do missions,’ and I was like, ‘No I’m not; no I’m not,’ but I wouldn’t even recognize to myself that I was having those thoughts because I was too scared,” Bradshaw said. “If I know what God wants me to do, do I want to be the person that says no to what God is wanting me to do, or do I want to be the person that says yes for the rest of my life? And I was like, you know, I want to say yes, and I know this is what He’s asking me, so I’m going to say yes.”

The sermon that convinced her of these thoughts is one that Bradshaw will never forget. All her life Bradshaw had felt this tugging towards international missions, yet she wouldn’t face the thoughts. She loved people and she loved God, but she wasn’t sure if she was ready to take a leap and go to another country to spread the message of the Bible. Yet, once she took that final step, her conviction was confirmed. She was set, missionary work was her calling.

“I don’t know if I want to live in another country, like, that is like my dream job, but I don’t know if that’s what God has blessed me with yet, maybe some day,” Bradshaw said. “I feel like right now he’s kind of pushing me to stay in the United States and working with the hispanic community here and just going on occasional mission trips.”

Throughout this process, Bradshaw retained her passion for the medical field. Her interest never wavered, even when she jumped around in her aspirations. Even during high school she wanted to be a physical therapist as a freshman, a doctor around junior year and then took a practical look at her future goals the summer after her senior year, which was when she settled to be a physicians assistant. She hopes one day she can use the talent and knowledge she gains to pursue medical missions.

Bradshaw’s compassionate and giving spirit helps her acclimate to the medical professions where she will be able to use those gifts daily when taking care of those in need. Her personality and passion pushed her into a career in which she can use those traits to make a living while also enjoying her job.

For some, though, figuring out what aspects of their personality will be most vital in pronouncing their careers brings about difficulty.

“I think sometimes when you’re thinking about a job, you want to think about your personality and what fits that, like do you want to work with people? Do you want to be in an office environment? Do you want to have flexibility to where you can schedule your day as you want? I mean there’s all sorts of things to think about when you’re going into a career, and ultimately I do think it’s important for you to go in the direction of what you are passionate about, sometimes at 16, I don’t think students know that yet,” Kersha said. “I mean there are so many careers out there right now, the world of work is changing so quickly that there are jobs that will be available in three to four years that no one even knows about right now, so that makes it different, it’s not like people are choosing one job and staying in that career for 40 years and then retiring like it was 20 or 30 years ago.”

In addition to exponentially growing job market, the increase in number of undergraduate major options for college students has sped up during the past decade. According to an article in The New York Times, U.S. colleges and universities reported over 1,500 academic programs to the Department of Education in 2010, 355 of which were added within the last 10 years. The University of Missouri-Columbia alone has 280 to pick through. This makes narrowing down potential job options a much more difficult task.

Up to 80 percent of students going into college aren’t certain of their major, whether they declared one or not,according to research conducted by Penn State and other institutions. Additionally, the research showed that up to 50 percent of all students in college will change their majors at least once, if not multiple times, before walking across the stage and receiving their diploma.

“There are a lot of students who change their majors multiple times. And I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad thing,” Kersha said. “I know it makes parents somewhat uncomfortable sometimes. I mean obviously you want to go to a school that has a major that you’re going to want, but I think more so than anything, having a direction but maybe taking a little of the pressure off because those first two years of college you are taking primarily core classes, English, math, science, social studies, and then you can take a few smattering of electives, that once again can help you figure out, ‘Oh no, I don’t want to do this.’”

After experiencing two years of college, Bradshaw is still just as devoted to medical missions and being a Physician’s Assistant as she was when she first started college. She has learned a lot though, especially that if she hadn’t pursued her passion she wouldn’t be as satisfied or feel as fulfilled as she now does.

“I would tell somebody … don’t go in undeclared or don’t take a bunch of classes and waste two years and spend a ton of money,” Bradshaw said. “Pick something that you have a slight interest in it and pursue that because … if you have a passion for it and you’re taking those classes, the passion grows.”

By Brittany Cornelison

[/tab] [tab title=”Balance”] [heading size=”20″]Music now, music after high school[/heading]

For as long as she can remember senior Katie Wheeler has been singing. She has gone from singing in church choir as a small child, to seventh grade show choir at gentry middle school, and now to swing dancing in RBHS city lights show choir this year.

“I know if I don’t do something with music I will not be happy in life,” Wheeler said.

Wheeler is a third year show choir member, having spent her sophomore and junior year in RBHS’s women’s show choir, Satin ‘n Lace, and her senior year in City Lights, RBHS’s mixed show choir. Having tried everything from journalism to Rock Bridge Reaches Out, wheeler has found her home in the music hallway, and plans to remain in the field.

Often in high school, students like Wheeler choose to participate in activities not just to make a more enjoyable high school experience, but to prepare them for their future career.

Perhaps the most prominent examples of specializing in one area are the students in the music department. Show choir and marching band students are devoted to their respective activities, often spending late nights and Saturdays at school working on their craft, outside of their 90-minute class period every other day. For many, the fascination began early on.

“I stopped singing in eighth grade at Jeff because I just was not a fan of the music program,” Wheeler said, “but I was informed that we would have to continue to sing in ninth grade to be in show choir, so I did choir in ninth grade.”

Wheeler knew from even her middle school show choir years that it was something she wanted to do for her time in high school. After trying journalism and Rock Bridge Reaches Out, she just came back. Wheeler chooses to spend a significant portion of her time in Show Choir. From morning rehearsals before school at 8 a.m. to evening rehearsals until 7:30 p.m., approximately 60 other performers and she work together to perfect a show for competitions beginning in February. For the past three years, Wheeler estimates she has spent an eight hours a week on show choir.

Show choir students spend 50 minutes every other morning, and one to three hours after school once or twice a week, with Saturday competitions second semester. Members of the school’s marching band have three hour rehearsals every other morning during first semester to prepare for Saturday competitions, which last through November.

Senior trombonist Amanda Eaton said she spent around 28 hours a week rehearsing with marching band in the fall in addition to participating in Show Choir Combo during second semester. In addition to band, she takes four Advanced Placement classes. Eaton can hardly miss school, even for band, without getting behind.

“My teachers still expect me to make up my work for today and complete homework for Monday, but there really isn’t time for it.” Eaton said after a Friday and Saturday marching band competition, “Sunday will be spent catching up on sleep and school work and college apps.”

As a senior, Eaton applied to colleges while keeping up with her classes and extracurricular activities. Even though band is a curricular class, most practice takes place before and after school while school hours are spent rehearsing as a full ensemble. Because her musicianship demands a large amount of time, Eaton feels she has no life outside of band.

Even though Eaton enjoys playing music, she doesn’t plan to continue devoting so much time to the arts after high school. Instead, Eaton wants to earn a degree in biology as an undergrad and attend medical school. While her ultimate goal is to become a neonatologist, Eaton still values her time spent learning music.

“I would … like to do something with music in college,” Eaton said. “I mean, I’m not getting my major in music or anything.”

Eaton participates in band for the fun of it, not because she wants to pursue a musical career in the future. Wheeler, however, plans to incorporate her high school experience into her career by studying music therapy.

“I really want to help people. Music therapy is working with autistic kids or dementia patients and helping them make choices or communicate… because the patient sets their own goals,” Wheeler said, “I find it really interesting, and it’s starting to boom, so there’s gonna be a lot of jobs in it. It’s realistic and music and helping people, so it’s all things that I need.”

In order to pursue her dreams and help others, Wheeler must keep her grades up in her final year of high school. In order to study music therapy, she must apply to both the main college and the music department of the school. This means both grades and musical ability matter when applying and auditioning for her choice school.

Director of guidance Betsy Jones worries some students might dedicate too much time and effort to their extra curricular activities, however, and allow their grades to drop before they apply to college.

“[Colleges] look at core GPA. When they’re calculating a student’s GPA for admissions they’re not looking at the four bands, or the four choirs, or the four journalism classes,” Jones said. “They’re only looking at English, math, science, and social studies, world language, maybe one elective class.”

For students like wheeler, who will have to audition for their place in school, the grades are on top of multiple other things. In order to be accepted into a music therapy program, wheeler will have a lot of hoops to jump through. Her dream school, Appalachian state, has rejected her from their music program, leaving her to apply elsewhere.

“I also have to audition, and get accepted and for a lot of [schools] you have to be accepted to the school and music school,” wheeler said, “it’s double the application and double the interviews and the recommendations”

With this in mind, Wheeler and Eaton still devote their time to their craft. While it might not help them take the ACT, activities like marching band and show choir present opportunities for life lessons that will last a lifetime. At the heart of these activities, is the power of a team, leadership abilities and discipline necessary to succeed in the real world.

“You’re learning responsibility; you’re learning accountability to other people,” choral director Mike Pierson said. “Both of those things are an important part of every, every part of our society. It encourages you to maintain a good schedule as far as when you’re not in rehearsal you’re doing your homework, it doesn’t allow necessarily for a lot of sitting around watching tv, or you know, playing video games, that sort of thing.”

Wheeler agrees, noting that the “21st century skills” involved will be useful to her in the future.

“Show choir teaches you a lot, it’s how to work with people you wouldn’t normally get along with, and… communicating with people, it teaches you a lot about that,” Wheeler said, “and I think those are just really useful things to have in this century.”

By Madi Mertz

[/tab]

[tab title=”Passion”]

[heading size=”20″]Playing for enjoyment, reaping healthful rewards[/heading]

When Evan Schaffer was in third grade, he played violin for the school orchestra. His involvement in music sparked his curiosity in the arts, which led him to try out various musical instruments.

Over the years, he learned how to play violin, bass guitar and french horn. When he reached sixth grade his school asked him to choose between orchestra and band; he dropped the violin in favor of the french horn.

At that time, Schaffer found concert band music more intriguing than orchestral music.

“I guess orchestral music, there just weren’t as many part whenever I was in it…. it has only strings and everything because it was sixth grade,” Schaffer said. “A little blow, that’s when there wasn’t any wind instruments or anything. So that’s one of the reasons there are a lot of band instruments comparing to orchestra instruments.”

The decision to stick with band eventually lead Schaffer to achieve prestigious honors in high school. After more than six years since he joined band, he received a national honor. Last summer, after making state band, he recorded a solo, “Hunter’s Moon” by Gilbert Vinter. He had practiced for over a year with his private lessons teacher, Dr. Marcia Spense, and he submitted his piece as his audition for the national honors band. He mailed in his tape and waited until received the email that told him he made the band.

“I was kind of surprised. I wasn’t expecting to get in.” Schaffer said, “It was recording so I didn’t have that much of a feeling. I just kind of went to a lesson and rehearsed it and recorded it with my teacher and then mailed it to them. I didn’t really expect to hear much back from them.”

Along with the honors of membership, playing in band helped Schaffer grow as a musician. After starting orchestra in third grade and playing in band from sixth grade on, he developed a passion for music, and his participation also added to his social life.

“I think playing in music builds community with other people,” he said. “So whenever you get to play music with other people you [build friendships]. was a fun experience”

In addition to building community, music can bring about positive health benefits. According to the Association of Psychological Science, playing a musical instrument affects the musician’s brain positively by releasing dopamine from the striatum, a part of the brain with pleasure-related stimuli.

Robert Zatorre, professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Montreal Neurological Institute, said, music is strongly associated with the brain’s reward system and it is the part of the brain that tells us if things are valuable, important or relevant to survival.

In an experiment where 804 people from Barcelona listen to music, he observed the activities of the brain’s reward system and said the emotion evocation plays out stronger in the reward response. He said the “reward associated with music has not been traditionally related to its capacity to provide primary reward. In this regard, some authors have suggested that music has a sexual-selection origin similar to the songs produced by songbirds.”

“According to these [authors of sources], music would act as secondary reinforcer related with sexual reward,” Zatorre wrote. “However given the many situations of real-life music listening where a sexual selection hypothesis could not apply, other factors must clearly play a more important role. Recent studies suggest that the hedonic impact of music listening is driven by its intrinsic ability to evoke emotions.”

For high school musicians, music can provide a helpful and healthy distraction from the everyday stresses of classes. Junior Emily vu, who played piano for years, joined band and learned to play the alto saxophone in sixth grade. Vu said playing both in school and outside of school helps relieve her school-related stress by clearing her mind.

“Whenever I go to a sax lesson it really helps me forget about all the other things I have to do,” Emily Vu said. “Also, being a part of the band at school is also great because I’ve made a lot of new friends from this past marching season. Music has helped me accomplish things, inside and outside of band.”

Similar to Schaffer, Vu became interested in playing musical instruments in third grade when she joined orchestra. She watched her older brother play piano, and his musicality inspired her to play as well. Now she plays guitar in the RBHS jazz ensemble and saxophone in wind ensemble. In her early years as a musician she didn’t practice very much, but in the past year she practiced 30 to 40 minutes a day when she auditioned for district band on alto saxophone and district jazz band on guitar.

For senior Daniel Shapiro, music is important both in and out of school. Last year alone he performed with the Jazz Ensemble for the Jazz Education Network and the Missouri Music Educators Association all-state conference in addition to participating in CAPERS, an all school talent show. For CAPERS, Shapiro and his friends put together a funk band and played the closing act at. He considered this event to be the most memorable musical activity he ever did.

Playing music “has certainly changed my life. Personally, I love playing in front of crowds and we had a packed house with all the band directors from around the state plus some all state musicians. We played really well and the adrenaline was awesome,” Shapiro said. “It’s a nice way to get away from the daily grind in a way because music is just fun to play, really. Much of what I do in my free time involves music as well, so I really have become immersed in it.”

By Jay Wang

[/tab]

[tab title=”Preparation”]

[heading size=”20″]CACC students leave RBHS with a head start on career planning[/heading]

Every day senior Keeley Houghton makes the trip across the RBHS north parking lot to the Columbia Area Career Center. She and 12 other students from varying high schools around mid-Missouri change into scrubs and tennis shoes for their next class: Emergency Medical Technician-Basic. For the next two hours Houghton and her peers will learn and practice how to handle emergency situations like detached limbs, protruding organs and an irregular pulse.

Houghton and most of the other students in the class are sure that they want to pursue a future in healthcare. Though she is unsure which field of medicine she will go into, Houghton took the class to perfect her skills and learn more about the different facets of healthcare, she said.

The class “puts you in real situations,” Houghton said. “It puts you right up there in action – you are actually doing hands on stuff. With the [agricultural] classes, like welding, they have you do horse trailers and help build stuff. In firefighting they actually do fire control stuff and all the classes have real experiences with their field.”

“Preparing today’s learners for tomorrow’s careers” is the mission of the CACC. The CACC uses a hexagon as its logo, with a different category of professions for each side. They include Business, Management and Technology, Health Services, Human Services, Arts and Communication, Engineering and Industrial Technology and Natural Resources Agriculture. By offering more than 80 courses that fall under one of these six categories, the CACC’s vision is “to empower individuals to achieve career and academic success, be vital to the educational and economic growth of our community, and a national leader in career and technical education,” according to their course catalog.

Rather than provide a traditional education, the CACC focuses on a more practical and hands-on approach. RBHS alumnus, Matt Gibbons, graduated in 2010, and took Certified Welding 1, 2 and 3 during his high school career. Gibbons, now working with HMT Innovative Tank Solutions, said that his CACC classes kickstarted his welding career.

“I think Career Center classes are almost better in some ways than your regular classes because they’re hands on,” Gibbons said. “Basically, you’re not reading out of a book, you’re not writing stuff down. You get to put your hands on the material so you’re working with it and everything, and it’s really beneficial for future jobs.”

The CACC strives to guide all students in achieving the academic and technical skills necessary to attain their goals – whether those are continuing education or employment opportunities in high demand, emerging or established fields, according to the 2013-2014 Course Catalog.

Additionally, students can often use CACC courses as dual credit or articulated credit at select universities near Columbia. Laser tech and Photonics 1 and 2 teacher Richard Shanks said often students who take CACC classes and attend technical schools and two-year universities do better than other students who don’t. Many of the degrees that the CACC caters toward often leave students with high-paying initial salaries, Shanks said.

“When they showed me the data and statistics of it, it really just astounded me, and I didn’t understand it,” Shanks said. These classes “are more than viable. I think they are essential for success later in life. A four-year-degree is great and good for some, but I think that the two-year-degrees that all of these classes can prepare you [for] more are efficient.”

From 1990 to 2000, full and part-time enrollments at two-year institutions rose from 5.2 million to 5.9 million, according to a study the National Science Foundation conducted in 2004. The same study stipulates that on average, 44 percent of science and engineering graduates attended community colleges. After graduation, Giddons went straight to working for FedEx, but also considered Tulsa Welding School and Missouri Welding Institute. Though he did not attend a two year or a four year university, many of his peers at RBHS who also took CACC classes are doing well, he said.

“I know at least 10 people who went to the Career Center classes for specifically welding and they’re now out in the field making good money, providing for their family,” Giddons said. “And that goes with really any other class [at the CACC].”

Senior Isabelle Mitchell is in Advanced Animal Science at the CACC this year because she has wanted to be a veterinarian since she was eight years old. Mitchell said that she took the class as a way to reinforce her interest and passion in the profession. So far, she has loved the class and everything they have learned; it is helping her focus her areas of interest.

“It won’t make it clear what career path for teenagers they want to go into necessarily,” Mitchel said, “but it will definitely help make clear what their strengths and weaknesses are and what they are interested in, what their ambition is.”

Shanks agrees with Mitchel that CACC classes can help lead them to develop their interests for future jobs. Though some may think that the classes would, in Shanks’ words, be “third world population type classes,” in actuality, they are some of the most high-tech classes, he said. Shanks thinks students should take into account that these classes can give them the means necessary to enter similar industries and lead them to jobs they would find enjoyable.

“We teach careers,” Shanks said. “We teach people how to work, what to expect in the work and on a real job, how to approach and how to get a real job.”

By Trisha Chuadhary

Additional Reporting by Justin Sutherland

[/tab]

[/tabs]